So you’ve seen the filters, the dances, the dreamy outfits—but what does Douyin actually mean? The name itself, 抖音 (Dǒu yīn), literally translates to “shaking sound.” It sounds simple, almost mechanical. But in practice, it’s anything but. That “shaking” is the scroll, the endless flick of the thumb. And the “sound”? It’s the beat of meme remixes, voiceovers, livestream rants—tiny digital pulses that now shape how China laughs, argues, buys, and even dates. This isn’t just TikTok with Chinese subtitles. Douyin has evolved into something stranger, more localized, more wired into everyday behavior. In the sections ahead, we’ll break down where the name comes from, how it became China’s cultural accelerant, and what it means if you’re just now stepping into its world.

Douyin

Tracing Douyin’s Origins to Understand What It Really Means

What “Douyin” Means in Chinese—and Why It Matters Culturally

You’ve probably heard people say “Douyin is just Chinese TikTok.” But even the name gives away the difference. "抖音" (dǒu yīn) literally means “shaky sound” or “vibrating music.” It’s a weird name at first. But if you’ve ever used the app, it makes complete sense. You hear a beat before you notice the visuals. Scroll through a few clips, and you’ll realize—sound drives the entire ecosystem. From lip-syncs to remix battles, Douyin is built on audio hooks that hit first.

In China, that matters. Because historically, platforms like QQ or Renren were more text- or image-heavy. Douyin flipped that. It prioritized rhythm over structure, emotions over logic. One viral clip could launch a song into stardom—no promo budget needed. Suddenly, everything from traffic cops dancing in Hunan to moms doing makeup tutorials in Henan had a soundtrack. And that soundtrack was shaking—“dou”—through your phone.

And here’s the thing: to a Chinese audience, “Douyin” sounds playful, a bit childish, almost rebellious. Not trying to sound professional. Definitely not aiming to be WeChat. Just wants you tapping your foot before you even notice.. That’s the brand DNA. That’s why the name works—because it’s not trying too hard.

ByteDance’s Vision: Why Zhang Yiming Created Douyin First, Not TikTok

Douyin wasn’t born out of some tech arms race with the West. It started, oddly enough, as a domestic experiment. ByteDance founder Zhang Yiming launched Douyin in 2016 for a very specific reason: young Chinese users were scrolling less on WeChat and more on short-form video apps that offered quick dopamine hits. Zhang saw a gap—not in content, but in control. Existing platforms were messy. What if you could build one that felt cinematic and addictive but still played nice with China’s content regulations?

The early Douyin interface was smooth, clean, almost sterile. Music mattered. Filters mattered. The vertical scroll? That was the magic. ByteDance’s engineers didn’t just study Chinese Gen Z habits—they practically obsessed over the milliseconds it took to swipe. Every delay, every bounce animation was tested to keep users in. It’s no accident Douyin succeeded before TikTok—TikTok is technically its clone, made for export.

I wouldn’t call Douyin the first short video app in China, but it was definitely the first one that felt like it belonged on a flagship phone—not a sketchy download from an off-brand store. Zhang wasn’t trying to go viral. He was trying to build the future mall, the future stage, and—some say—the future newsstand, all in one swipe.

From Dance Videos to National Phenomenon: The First Viral Moments

In Douyin’s earliest days, it wasn’t about brands, hauls, or makeup hacks. The app first exploded thanks to what users called "洗脑神曲"—brainwashing songs. The earliest viral clips were often just random teens dancing to repetitive techno-pop, usually filmed in neon-lit parks or underground mall corridors. The shaky camera work wasn’t a bug—it was part of the vibe.

One of the first big waves came in late 2017 when a clip of a boy dancing to “海草舞” (Seaweed Dance) caught fire. The move was ridiculous—arms flopping side to side like seaweed in the tide. But it was so catchy that people from office workers to school kids started filming their own versions. You couldn’t walk through a subway station without hearing someone humming it. Suddenly, everyone knew what Douyin was—even people who didn’t use smartphones much.

The early algorithm was ruthless. It would push content hard if it sensed people rewatching, commenting, or mimicking. So creators learned fast: edit tight, keep it weird, and pick a sound that sticks. No one planned to go viral—but when it happened, it happened fast. That speed—plus the strange, almost DIY look—gave Douyin a rough charm that TikTok never really copied.

Are you ready to try this app? Don’t miss our full guide: What Is Douyin? Your 2025 Breakdown of the Chinese TikTok.

Why Douyin Isn’t Just ‘TikTok in Chinese’—And What the Name TikTok Really Means

“TikTok”: A Name That Tells Time, Rhythm, and Virality

There’s a sound to the word “TikTok” that feels mechanical. Like a clock. That’s no accident. When ByteDance chose this name for Douyin’s international version in 2017, the branding team wanted something rhythmic, global, and time-driven. Something that suggested motion—specifically short, looping motion.

“TikTok” mimics the ticking of a clock, but it also mirrors what happens inside the app: time flies, videos are bite-sized, and virality has a beat. While “Douyin” evokes vibrations, emotion, and sonic energy from a local angle, “TikTok” feels cleaner, more abstract. It’s optimized for global ears.

Interestingly, some Chinese netizens joke that “TikTok” sounds like a kid’s toy. And in some ways, it behaves like one: fast feedback, bright visuals, addictive loops. But the name works internationally because it avoids cultural specificity. There’s no Chinese language baggage, no political overtones—just a clock, ticking toward the next viral thing.

Tik Tok

ByteDance’s Split Strategy: One Engine, Two Worlds

One of the biggest misconceptions about Douyin and TikTok is that they’re just different skins on the same app. In reality, they’re more like siblings raised in different homes. Same DNA (the algorithm), but very different upbringings.

ByteDance didn’t just translate the app—they rebuilt it. Douyin is tied to China’s data laws, payment systems (like Alipay integration), and censorship filters. TikTok, meanwhile, runs on separate servers, has Western content moderation, and no access to Chinese domestic APIs.

Why the split? In part, regulation. China’s firewall won’t allow cross-border user data flow. But also, ByteDance realized early that Chinese and global audiences scroll differently. What hooks a teen in Hangzhou isn’t always what clicks for someone in Toronto. So the company let both apps evolve independently—testing features in one before porting them, if at all, to the other.

So yes, they share the algorithm blueprint. But if you ever use both apps side by side, the differences will smack you in the face: Douyin is louder, faster, more saturated. TikTok feels smoother, safer, and slower—like a cousin that took up yoga while Douyin went clubbing.

How Users Perceive the Brand: What Does Douyin Sound Like to Locals?

Ask someone in Beijing what “Douyin” means to them, and they probably won’t say “a short video app.” They’ll say something like “time killer,” “trend maker,” or “where I learn dance moves.” In other words, Douyin has become a behavior, not a brand.

In China, “刷抖音” (shuā Douyin) is a verb. It means to enter that zone of infinite scroll, snack-sized entertainment, and emotion-driven content loops. It’s like how “Google” became a verb in English. That kind of linguistic shift reveals power—it means the app isn’t just part of the ecosystem, it is the ecosystem.

Interestingly, the word “Douyin” carries a certain tonal weight. It’s got two sharp syllables. The first—“Dou”—sounds abrupt, like a tap or bounce. The second—“Yin”—feels softer, more musical. Together, they form a rhythm. It literally sounds like how the app moves: bounce, echo, swipe.

It’s hard to imagine “TikTok” achieving the same cultural saturation in China. Not because it’s a worse app—but because it lacks the local flavor. Douyin sounds like something invented inside the culture. TikTok still sounds… foreign.

Douyin Fashion Explained: Is It a Style or a Statement?

Why Douyin Outfits Look Different: Filters, Editing, and Fast Cuts

Douyin fashion isn’t about what you wear—it’s about how it moves. That sounds weird, maybe. But if you spend even ten minutes on the app, you’ll notice: clothes aren’t just displayed, they’re animated. Long sleeves whip across the screen in slow motion. A jacket flips open just as the beat drops. A full outfit reveal happens in a single, whip-pan cut that feels more like choreography than fashion.

Part of this is editing—Douyin popularized a kind of hyperactive jump-cut aesthetic, where fast changes feel smoother than slow pans. But part of it is the filters. There's a “beauty cam” culture in China where people expect digital polish. Colors are boosted, faces slimmed, backgrounds blurred. So that simple streetwear? It glows.

You might walk past a Douyin shoot on a side alley in Suzhou or near the art zone in Beijing. What looks like someone pacing awkwardly or twirling pointlessly becomes, on-screen, a sleek fifteen-second aesthetic bite. In real life it’s awkward. On the app, it’s aspirational. Maybe that says something about the way Douyin reframes reality—faster, brighter, more curated than you'd expect.

Hanfu, Guofeng, and Digital Makeovers: The Deep Roots of Douyin Aesthetics

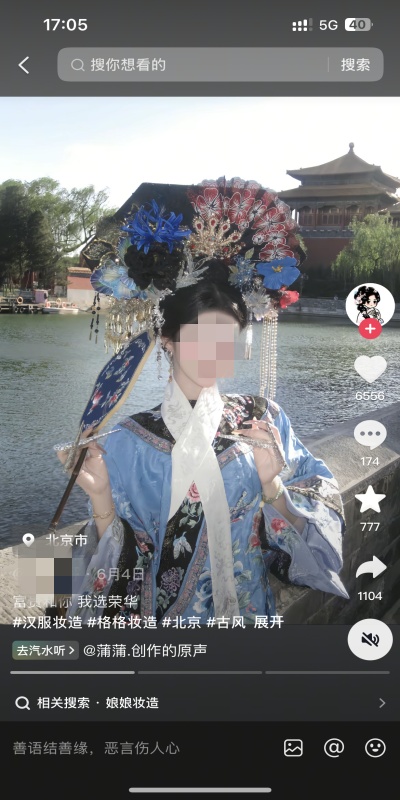

If you scroll deep enough on Douyin, you’ll eventually hit a video that feels... ancient. Not dusty—but timeless. A girl in a flowing hanfu walking past a tea field in Wuyuan. A guy in a jade-green robe pouring wine under a waterfall, paired with a traditional zither loop. This is “Guofeng” (国风), or “national style”—a genre that pulls visual cues from Chinese history, poetry, and period dramas.

What’s fascinating is how modern it feels. These aren’t museum pieces. They’re shot with drones, cut with EDM, sometimes even paired with makeup tutorials or cosplay jokes. The result is a hybrid of old and new, tradition and play. Hanfu on Douyin isn’t just fashion—it’s performance, nostalgia, and identity all wrapped in one.

And the demand is real. According to a 2024 report by Xiaohongshu (Little Red Book), hanfu-related hashtags generated over 9 billion views in just six months. Offline too, people wear hanfu to theme parks, Starbucks, even on the subway. Douyin didn’t invent this trend, but it amplified it—and shaped it into something global-facing, aestheticized, and emotionally loaded.

Douyin’s Beauty Standards: Do They Reflect or Distort Real Life?

There’s a joke that on Douyin, everyone’s face looks like a “default filter.” Big eyes, small chin, pale skin, airbrushed vibes. And to be fair—those filters are real. Douyin’s beauty effects can reshape your face in real time, slimming your nose or making your cheekbones pop with a single swipe. Some people say it’s fun. Others say it’s warped.

The tension is obvious. On one hand, Douyin has opened up the stage to millions. You can post in your pajamas and still go viral. But on the other, there’s a quiet pressure to fit the platform’s unspoken ideal. A “Douyin face” now exists—sharp jaw, blurred pores, a glossy aura that looks nothing like real skin. For teens especially, that line between real and edited can get... fuzzy.

Still, it’s not all bleak. There’s a growing counter-movement too. Some creators now tag #nofilter or show their editing layers as tutorials. Others intentionally lean into chaos—wacky filters, ugly face transitions, parody makeup. Maybe Douyin’s aesthetic isn’t fixed—it’s elastic. But if you’re new to it, just remember: what you see isn’t always what you get.

- Tik Tok Home Page

- Hanfu Makeup

How Douyin Fuels Consumer Trends Across China

The Power of Live Shopping: Makeup, Clothes, and Real-Time Sales

Imagine scrolling through a livestream of a girl in Guangzhou applying lipstick—and suddenly, a “Buy Now” button pops up mid-sentence. You tap it. Ten seconds later, the order’s placed. That’s not an ad. That’s commerce, Douyin-style.

This “live shopping” model, or 直播带货, took off hard around 2020 and hasn’t slowed since. Unlike Amazon Live or Instagram Shopping, Douyin’s approach is deeply embedded in its content. A makeup artist isn’t selling makeup—she’s showing how it wears, smudges, glows in natural light. A farmer isn’t pitching apples—he’s cutting them open on camera and letting the juice drip.

Trust is built through pacing. You watch someone test a hair curler for ten minutes before deciding it’s worth the ¥68.80. You read real-time comments: “这个好用吗?” “回购第三次了!” There’s peer validation, not just brand talk. It’s messy, sure. And it can be overwhelming—sometimes creators sell 20 items in 10 minutes. But this chaos is part of the charm. In Douyin’s world, shopping doesn’t interrupt content. It is the content. And when it works, it’s addictive in a way e-commerce platforms haven’t fully figured out elsewhere.

Influencer vs. Creator: Who Sets the Tone on Douyin’s Fashion Feed?

On Western platforms, the word “influencer” usually means someone with millions of followers and a carefully curated feed. On Douyin, the waters are murkier. There are influencers, sure. But creators—小博主, part-time editors, people who film during lunch breaks—are the ones shaping trends.

One week it’s a hairstylist in Nanning doing color transitions in one-take reels. The next, it’s a dad in Xi’an filming his daughter’s outfits while adding dry, hilarious commentary. None of them are huge names. But their styles go viral, because they feel “useable.”

That’s the difference. Douyin trends don’t feel unreachable. You’re not watching a celebrity with a glam squad; you’re watching someone who shops on Taobao and edits with CapCut. Sometimes they’ll even show their failed takes, or laugh at the fact they used the wrong filter. The vibe is: “Hey, you could do this too.”Of course, some creators do become mega-stars. But even then, the tone stays grounded. It’s the mix of aspiration and approachability that makes Douyin fashion feel more like a mirror than a magazine spread.

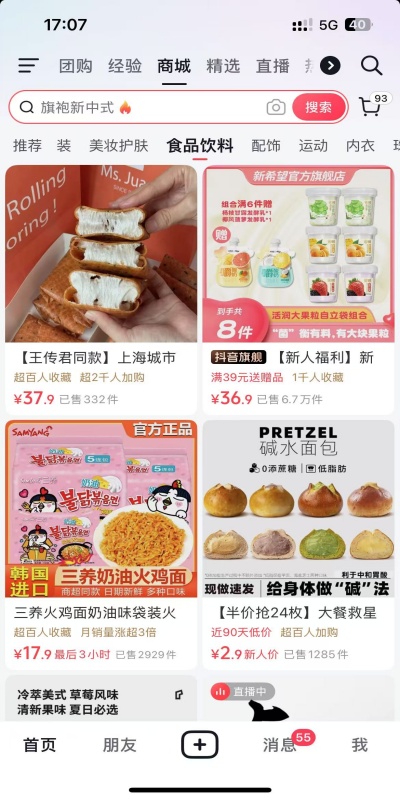

From Local Markets to Luxury Brands: What People Actually Buy via Douyin

Scroll past the Hanfu shoots and viral dances, and you’ll find something quietly fascinating—what people actually buy. It’s not just Dior lipsticks and Dyson hairdryers. It’s also ¥9.90 panda slippers, ear pick cameras, sachets of chili oil, or even full-on wedding photo packages.

Douyin’s recommendation engine doesn’t care what tier a brand belongs to—it cares about click-throughs and comments. That’s why a no-name T-shirt brand from Fujian can outsell Adidas during a flash sale. The playing field is flat, and weird wins.

Luxury brands noticed. Louis Vuitton and Prada have official accounts now. But even they adapt to the tone—less gloss, more “real-time try-ons,” sometimes using local dialects. You don’t sell status on Douyin. You sell a feeling: surprise, comfort, satisfaction. Sometimes it’s chaotic—like buying something just because the comment section said “冲冲冲!” But it’s also oddly democratic. Douyin isn’t just selling things—it’s telling us what Chinese consumers actually want in 2025. And often, the answer isn’t what brands thought.

- Douyin Mall

- Hairstylist’s daily photo shoot

What Douyin Really Means in 2025 (And Why It’s Still Evolving)

Self-Expression or Soft Power? The Deeper Purpose Behind the App

It starts as fun—record a dance, try a filter, post a day in your life. But Douyin has always had layers. What feels like personal expression is often performing for the algorithm. And what looks like fashion is sometimes national branding in disguise.

Take the rise of guochao (国潮)—a revival of Chinese elements in streetwear, beauty, and design. On Douyin, you’ll see girls in Tang-inspired makeup doing smoky transitions or farmers doing rap videos in dialect. But behind it? Brands, sometimes even local governments, nudging content into a cultural export vehicle.

This isn’t just conspiracy talk. In 2023, several provincial media accounts—like “Henan Release” and “Shanxi TV”—began sponsoring Douyin creators to make “regional pride” content. Some did it well. Others felt… forced. But it showed one thing: Douyin isn’t just self-expression. It’s a stage where identity, commerce, and soft power blur.

Douyin as a Digital Mirror of Gen Z China

What’s trending on Douyin isn’t just a list of hashtags—it’s a snapshot of what Gen Z in China is feeling. You’ll see people talking about “躺平” (lying flat), joking about “打工人” (salary slave life), or posting their “emo” edits with vaporwave remixes.

And yet, it’s honest. On one hand, Douyin shows ambition: kids in Suzhou showing off coding skills or Shanghai teens vlogging their college hustle. On the other, you’ll find burnout confessions, therapy stories, even break-up montages with sad Mandarin ballads. It’s like watching a generation process life—one edit at a time.

Some sociologists argue that Douyin is Gen Z’s most accurate psychological diary. Not because it’s deep, but because it’s frequent. It records in fragments. And in those fragments, you get mood, tension, aspiration, irony. Not everything makes sense. But everything feels real. And maybe that’s what makes it stick.

Will Douyin’s Style Ever Translate Globally—Or Should It Stay Local?

Here’s the question no one seems to answer clearly: can Douyin’s aesthetic work outside China? Some say yes—just look at the growing “Douyin style” on TikTok, with its fast edits, dreamy filters, and fashion montages. But others argue that what makes Douyin work is its cultural tightness.

For instance, a viral dance on Douyin might be based on a 1980s Hong Kong movie theme. Or a skit might reference a provincial TV ad from the 90s. These don’t always translate. In fact, when foreign users stumble into Douyin clips, many say they feel lost—not because it’s bad, but because it’s too specific.

Still, that specificity is what gives Douyin its soul. Maybe it’s not meant to be exported like TikTok. Maybe its job is to stay weird, local, and unapologetically Chinese. In 2025, that might be Douyin’s edge—not global scalability, but cultural density. And if you get it, you get it. If not? That’s fine too.

- Ancient style short play

- Official Account

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Is “Douyin” just the Chinese name for TikTok?

Not quite. While Douyin and TikTok are owned by ByteDance and share similar algorithms, they operate in completely different ecosystems. Douyin is built for China—it runs on local servers, connects with apps like Alipay, and reflects Chinese internet culture closely. TikTok, on the other hand, was re-engineered for the global market. The vibes? Totally different. TikTok feels smooth and curated; Douyin is chaotic, loud, and deeply local.

Q: Why do people keep calling it “Douyin style”? What even is that?

It’s not just fashion—it’s a full aesthetic. Douyin style usually means fast edits, soft filters, dramatic poses, and clothing that moves well on camera. You might see Hanfu meets cyberpunk, or a girl turning in slow-mo with petals flying. There’s no strict rulebook—it’s about how something looks on video, not in real life. That dreamy vibe? That’s Douyin.

Q: I saw someone mention “Douyin makeup”—is that a real thing?

Yep, and it’s everywhere. “Douyin makeup” (抖音妆) is designed to flatter under filters and ring lights. It means glossy lips, sparkly under-eyes, blurred blush, and contact lenses that enlarge the eyes. Some people say it looks overdone IRL, but on screen? It glows. You’ll see tons of tutorials with hashtags like #getreadywithme or #抖音妆教程 teaching exactly how to nail it.

Q: Are people actually buying stuff through Douyin?

More than you’d think. In 2025, Douyin isn’t just for watching—it’s a massive shopping machine. Makeup, clothes, kitchen gadgets, even full wedding packages—users buy straight from livestreams. Creators don’t just show products, they demonstrate them in real-time. It feels personal, spontaneous, and oddly addictive. Some even trust Douyin shopping more than e-commerce sites.

Q: What makes Douyin different from Xiaohongshu?

Think of Douyin as speed and spectacle, and Xiaohongshu as slow and thoughtful. Douyin gives you 15 seconds of flair with background music. Xiaohongshu offers full product reviews, mini blogs, and curated travel diaries. They’re both powerful in China’s social media scene—but Douyin is for catching attention fast, while Xiaohongshu is about depth and taste.

Q: Is “Douyin boy” a joke or an actual style?

Bit of both. A “Douyin boy” isn’t just a guy using the app—it’s a very particular type: soft hair, clean jawline, moody eye contact, and maybe a slo-mo head turn. It’s become a stereotype and a meme. Some people love it. Others mock it. But either way, it’s part of how Douyin has shaped internet identity in China.

Q: Why is Douyin so addictive?

Short answer? The algorithm knows you too well. Longer answer: it combines fast-paced content with just enough emotional tug. One minute you’re watching a funny cat, the next it’s a girl crying over a breakup, then suddenly a livestream is selling lipstick. The scroll never ends—and that unpredictability makes you stay. It’s engineered for emotion, not logic.