Head over to Chaoshan—where roast pig crackles and the broths run deep, whether you’re drifting through Chaozhou or finding your way in Shantou. The air smells more of soy than soot. The menu? So crisp-sounding. No sizzling oil, no garlic overload. If you're new to chaoshan cuisine, you'll love the clear broths, the tender fish and shrimp, and those odd, gleaming jellies that shimmer like glass. A meal in Chaoshan doesn't shout—it earns your attention quietly. For instance, let’s begin with eight dishes so unassuming you almost miss their complexity. Quietly discover. Quietly admire.

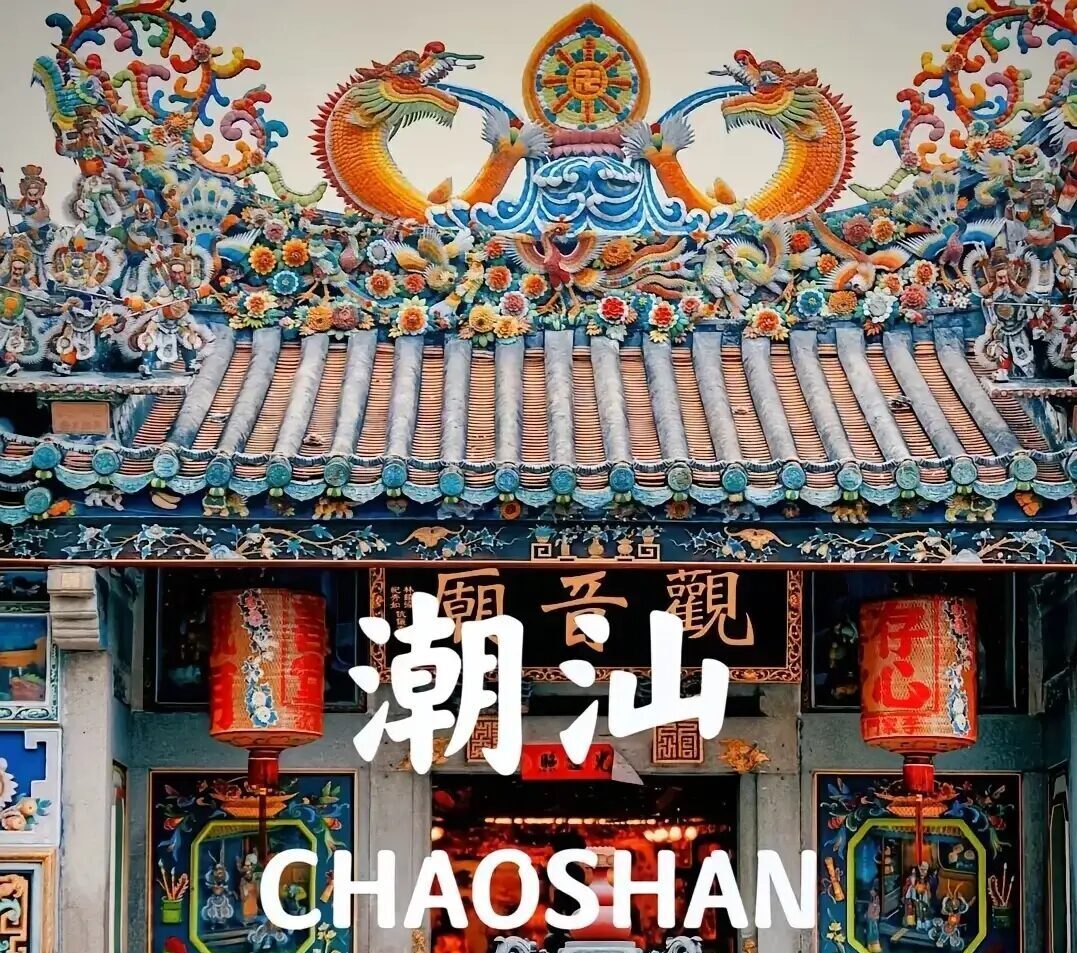

Traditional Attractions in Chaoshan

What Is Chaoshan Cuisine

Tucked in the eastern pocket of Guangdong province, there’s a cluster of cities—Chaozhou, Shantou, and Jieyang—locals call “Chaoshan.” It’s not just geography. The language sounds different (that’s Teochew, not Cantonese), and the food? Let’s just say it doesn't drown in sauces or hide behind chilies.

Chaoshan cuisine leans on a strange kind of confidence—it lets the ingredient speak first. Think clear broths, barely seasoned fish, tofu that tastes like, well, tofu. Some might call it mild, but that’s missing the point. The flavor sits quietly at first, then builds. There’s a sort of clean depth, hard to explain unless you’ve tasted steamed pomfret done right, or that cold crab with nothing but ginger and vinegar.

If you’re from somewhere like Germany, Singapore, or just tired of dishes shouting at your taste buds, this might surprise you in the best way. It’s delicate, but never weak. You just have to slow down and listen.

Teochew Cold Crab 潮州冻蟹

Teochew Cold Crab

You don’t need soy sauce or garlic when the crab’s that good. Teochew cold crab is boiled, chilled, and served with nothing but a dip of vinegar and sliced ginger on the side. That’s it. But when you crack open the shell and see that thick orange paste—not roe exactly, more like the “foie gras” of the sea—you’ll get it. It’s not about heat. It’s about texture, coolness, and this oceanic sweetness that kind of sneaks up on you.

Someone from Germany I once ate with compared it to chilled smoked trout, but gentler, creamier. Americans who like sashimi might appreciate how “raw” it feels, even though it’s fully cooked. The crab itself doesn’t scream freshness—it just quietly proves it.

Teochew-style Steamed Pomfre 潮式蒸斗鲳

Teochew-style Steamed Pomfret

It’s not flashy. There’s no bubbling oil poured over the fish, no garlic chunks, no soy sauce flooding the plate. Just pomfret, steamed gently with pickled mustard, ginger, and a bit of sour plum. The broth ends up almost like a tea—light, slightly salty, and kind of soothing in a way you don’t expect from fish.

For folks from Sweden or Canada, where clean eating and natural flavor matter, this would probably feel familiar. There’s zero grease, and the seasoning doesn't shout. It’s the kind of dish someone on a low-sodium diet could actually enjoy without compromise. And honestly, that soft bite of fish soaked in that tangy, almost medicinal broth? It’s oddly comforting.

Chives with Prawns 韭菜炒虾仁

Chives with Prawns

It looks simple, and it is. But that’s exactly why it works. Yellow chives—the pale kind, not the grassy green ones—sliced thin and tossed quick with fresh prawns, maybe a little oil, maybe some rice wine if the chef’s feeling generous. No garlic, no chili, just this gentle crunch and the kind of natural shrimp sweetness that makes you pause between bites.

I watched a couple from Singapore clean their plate before ours even landed. They said it reminded them of home cooking, just less oily. Someone from the Philippines at the next table asked the waiter for extra rice because, apparently, the juice at the bottom was too good to waste. Can’t blame them.

Chaoshan Beef Balls 潮汕牛肉丸

Chaoshan Beef Balls

They’re not just meatballs—they bounce. Literally. A real Chaoshan beef ball isn’t minced or blended. It’s made by hand-pounding beef—I mean guys literally whacking hunks of meat with wooden mallets until the texture changes. You can see them doing it in morning markets in Shantou, right next to the tofu stalls.

When dropped into hotpot, the balls don’t fall apart. They stay firm, with this springy, almost rubbery texture that some folks find strange at first—but it grows on you. Korean diners I met at a hotpot spot in Guangzhou said it reminded them of sundae or sausage, just cleaner tasting. And people from the Philippines? Well, they already love chewy textures—so this one’s an easy win.

Braised Goose 卤水鹅

Braised Goose (Lou Mei Style)

This one’s for those who don’t shy away from dark, rich flavors. Braised goose, or lou mei style, isn’t quick food—it sits in a vat of soy-based herbal broth, sometimes for hours, soaking up things like star anise, tsaoko, and other spices you’d probably find in a street market in Vietnam or Malaysia. The smell alone is hard to forget—sort of earthy, sort of medicinal, definitely bold.

When it’s done right, the skin’s glossy, the meat is almost loose, and every bite carries this deep, spiced-salty kick. It’s not sweet, not subtle, and definitely not trying to be “modern.”But yeah, it’s strong. Might not win everyone over on the first try. But if you get it, you really get it.

Pig Skin Aspic 猪皮冻

Pig Skin Aspic

It jiggles. That’s usually the first thing people say. But Teochew pig skin aspic isn’t some novelty wobbly dish—it’s slow-cooked pork skin and tendons, simmered until the collagen melts into a broth, then cooled into a translucent block. No tricks, no additives. Just time, patience, and a fridge.

If you’re from Germany, this might remind you of Sülze—that meat jelly you eat with vinegar and bread. But pig skin aspic is subtler. Less meaty, more about texture and that quiet richness from collagen. It’s not seasoned heavily, so you actually taste the gelatin itself, with maybe a splash of soy or vinegar on top.

Teochew Oyster Omelette 潮汕蚝烙

- 1Teochew Oyster Omelette

- 2Teochew Oyster Omelette

There’s this crackle when your teeth hit the edge—crispy, slightly oily, almost like the corner of a fried pancake. But then the middle? That’s where the oyster lives, soft and warm, tucked into egg and starch, just barely holding together. I still remember the crisp edges breaking under my teeth—the oyster was warm, barely set, and dripping soy sauce. It didn’t need anything else.

Is it greasy? A bit. Is it messy? Definitely. But that’s part of the fun. You eat it hot, standing maybe, leaning over a chipped plate, with your fingers a little sticky from the sauce. It’s not elegant, but it hits home.

Chaoshan Beef Hotpot 潮汕牛肉火锅

Chaoshan Beef Hotpot

You don’t really go for the soup. You go for the meat, and the moment someone drops a paper-thin slice into the bubbling pot, only to pull it out two seconds later—still pink, still trembling. That’s the whole point of Chaoshan beef hotpot. No heavy broth, no dipping sauce circus. Just you, your chopsticks, and a few quiet gasps when the marbling hits just right.

It’s especially popular with younger crowds—Korean students, Japanese travelers, even local Gen Zs who want something “clean but intense.” There’s something social about it too, passing plates around, calling dibs on the best cut.

If you’re curious about how it all works, Want more? Read our full Chaoshan beef hotpot guide here.

Beyond Chaoshan Cuisine: Daily Life and Dining Habits

Chaoshan isn’t just food—it’s a rhythm. In the old parts of Shantou or Chaozhou, you don’t even need a clock. The day starts with kettles clanking, tea leaves steeping in tiny covered bowls, and someone adjusting the coals under a battered water pot. Mornings smell like smoke, soy, and sometimes, ginger from the porridge stalls nearby.

And then there's the market—not glossy or touristed, but real. You see aunties negotiating over fish with plastic bags tied to their scooters, teenagers filming food stalls for Douyin, and vendors pounding beef on chopping blocks like it’s a drumbeat. You don’t browse here. You move with purpose. Even silence feels full.

At meals, people don’t say much. In Western homes, silence can be awkward. Here, it just means everyone’s paying attention to their bowl. It’s not cold—it’s focused. Chaoshan cuisine is good, sure. But it’s this quiet, almost disciplined way of eating and living that stays in your head long after the taste fades.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Do Chaoshan restaurants usually have English menus?

Not always. In larger cities like Guangzhou or Shenzhen, some Teochew spots might offer bilingual menus, especially near hotels. But in traditional Chaoshan areas like Shantou or Chaozhou, English is rare. You might get a laminated sheet with pictures if you're lucky. Locals often order based on what’s seasonal or fresh—so pointing at neighboring tables or asking for a recommendation (“tui jian” 推荐) actually works better than trying to read a menu.

Q: Is Chaoshan cuisine vegetarian-friendly?

Not exactly, but it depends. Traditional Chaoshan dishes tend to be seafood- and meat-heavy, especially with pork, goose, and beef. That said, you can find vegetable dishes like stir-fried greens, chive flowers with tofu, or even sweet yam paste (orh nee). Just be aware: even veggie-looking dishes may be cooked in lard or topped with dried shrimp. If you're strictly vegetarian or vegan, it's best to learn how to say “no meat, no seafood” in Mandarin or Teochew, just to be sure.

Q: Can I find Chaoshan ingredients if I want to cook it myself?

Some ingredients—like pickled mustard greens, soy-based braising sauces, or dried seafood—can be found in large Asian supermarkets abroad, especially in Chinatowns. But some of the more delicate stuff, like hand-pounded beef for meatballs or fresh lion-head goose, is really only available in Chaoshan itself. If you’re in China for a while, local wet markets in Shantou or Chaozhou are great for sourcing what you need—just be ready to haggle a little.

Q: Is it common to share dishes in Chaoshan restaurants?

Yes—always. Chaoshan meals are meant to be shared, family-style. You’ll rarely see individual portions unless it’s a street snack. In sit-down places, even the tea is poured for the group in rotation. Some restaurants will bring everything at once, others course it out slowly. Don’t feel pressured to eat fast—just let the table fill and pace yourself. And yes, it’s perfectly fine to use your own chopsticks to grab food, unless someone sets out communal ones.

Q: Are there any dining customs I should know before eating with locals?

A few, actually. First, don’t talk too much during meals—Teochew families often eat in near silence, not because it’s strict, but because food is taken seriously. Slurping, light chewing sounds? Totally normal. Also, don’t be surprised if someone stands up mid-meal to pour tea for elders. It’s a respect thing. Lastly, if someone insists you try a dish more than once—it’s polite, not pushy. Just smile, take a bite, and nod. That’s usually enough.