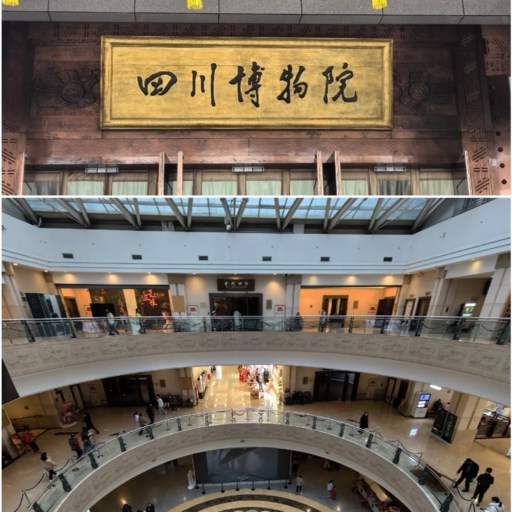

The Museum

Sichuan Museum is the largest all-purpose museum in western Chengdu that is situated along the Huanhuoxi Park. Sichuan is called the Land of Abundance, rich not only in nature but also in deep history and culture. Much of that heritage survives here. The museum covers about 12,900 square meters and houses over 260,000 cultural relics, including bronzes, pottery, calligraphy, and paintings. It clearly presents the province’s long history, with 14 exhibition halls displaying artifacts from the Ba-Shu civilization to modern Sichuan art. For visitors, Sichuan Museum offers more than a glimpse of the past—it’s also a window into the living rhythm and cultural depth of Chengdu today.

Quick Facts about Sichuan Museum

| Location | No. 251 Huanhua South Road, Qingyang District, Chengdu |

| Opening Hours | Tue–Sun 9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. (Closed Mondays) |

| Tickets | Free with ID or passport registration |

| Nearest Metro | Line 2 (Culture Park Station, Exit B) |

| Languages | Chinese & English labels available |

| Photography | Allowed except in certain galleries |

| Facilities | Café & souvenir shop on ground floor |

| Museum Layout | A three-story museum with over a dozen themed galleries, each showcasing thousands of relics. |

| 1F Highlights | Han Dynasty Pottery (202 BC – 220 AD); Multi-function Reception Hall |

| 2F Highlights | Ba-Shu Bronze Hall; Calligraphy & Painting Gallery; Ceramics Hall; Zhang Daqian Art Center |

| 3F Highlights | Tibetan Buddhist Art & Wanfo Temple Stone Sculptures; Sichuan Ethnic Minority Artifacts; Folk Arts & Crafts |

Why Sichuan Museum Is More Than Just Artifacts

- Neolithic artifacts

- Tang Tri-colored Glazed Pottery

A Museum That Speaks Chengdu’s Quiet Language

The afternoon light penetrates the bamboo outside the gate, casting pale stripes on the pavement. You hear first the sound — shoes brushing stone, a slow ripple of chatter, someone opening a thermos with a metallic click. Nobody’s rushing. That’s why Sichuan Museum is so perfect: It matches Chengdu’s rhythm instead of contradicting it. Across town, Chengdu Museum shines in glass and steel, proudly reflecting its skyscraper. Here the tone softens; the courtyard carries a hint of soil drenched by rain and glovesleeved air.

Locals still stop in even when they’ve seen it all already. “It’s the quiet I come for,’’ said a retired teacher I met on the stairs, not the relics themselves. Maybe this is why TripAdvisor gives the Sichuan Museum a 4.5-star average review — most patrons rave in the comments about how calm and unexpectedly spacious it feels inside. The staff seldom hovers, the volunteers smile readily and no one rushes you through a gallery. Families seek shade under the tall calligraphy banners as students draw bronze figures with stubby; pencils. Nevertheless, compared to the tenser, camera-conscious contrast between the crowded Chengdu Museum and Sichuan Museum (see below), this one feels lived-in, like an old story retold yet still warm.

How the Building Itself Tells Sichuan’s Story

Get closer, and the building starts to show its layers. The exterior walls are of a lightly grayed brick, devoid of smut but not texture — the sort that takes daylight without glare. The rooflines are based on the tiled, rolled-eaved houses of old Sichuan courtyard dwellings, and from the upper corridor one gets a view over treetops to see an eternal flash of green from Huanhuaxi Park. The design doesn’t set out to impress — it oozes familiarity. That’s what good Sichuan Museum architecture does: reflects the province itself, steady, practical with a layer of damp clinging to the edges.

If you enjoy tracing Chengdu’s cultural rhythm from ancient halls to temple courtyards, you might love reading about its legendary heroes and timeless architecture at Wuhou Shrine Chengdu: A Timeless Journey into the Three Kingdoms Legacy.

Inside the Sichuan Museum – Galleries You Shouldn’t Rush Through

Han Dynasty Pottery & Portrait Bricks

You’ll see it just beyond the main hall—rows of terracotta figurines with cracked faces that remain strangely expressive, as though carved yesterday. This section of Sichuan Museum’s display of Han Dynasty burial art includes a shrine-shaped coffin, pottery, and human figures. It feels less like a tomb and more like a glimpse into daily life. The pottery men hoist chickens, beat drums, and ride carts, while one woman stands laughing mid-motion. TripAdvisor visitors often marvel at these “unexpectedly vivid figures,” and they’re right—each one seems caught mid-gesture, whispering that life for those ancient Sichuanese people wasn’t what emperors wanted remembered.

You feel warmth here, not the usual solemn silence found in historical halls. The clay holds the tawny ocher color of Sichuan soil, and the light remains soft, almost domestic. It’s easy to picture artisans shaping these figures in sunlit courtyards, smoke rising from kilns, roosters crowing nearby. Among all exhibits in the Sichuan Museum, this room feels the most human. It’s less a history lesson and more like a quiet reunion. Take your time; you’ll leave remembering faces you can’t quite forget.

Bronze Wares of Ba-Shu Era

If you have visited the Sanxingdui Museum or even the Jinsha Site, you will sense this thread leading straight into this gallery. The Sichuan Museum bronze collection gathers artifacts that bridge those early cultures — bronze masks with gold leaf, ritual drums, and animal-shaped vessels with twisted horns that catch the dim gallery light. They seem at first to come from alien hands, but as you stand there looking, they slowly feel familiar, as though that wild creativity still defines Sichuan today.

The curators display them under pale lighting, and shadows slip like smoke across the engraved lines. You can almost feel the hands that pulled these items from river mud, cleaned them carefully, and restored their lustre. For anyone following the Jinsha Site Museum connection, this room becomes a quiet climax. It proves that the Ba-Shu people didn’t mimic Central Plains culture; they created their own. The air smells faintly metallic here, and when you step back into brighter halls, the world feels fresher again.

Zhang Daqian Art Gallery

I didn’t plan to spend 40 minutes at this booth. A tiny sign with the words “Zhang Daqian Art Gallery,” so unassuming you might as well miss it, but once you’re inside, everything seems to slow down. The ink paintings drape open and breathing, mountain mist evaporating into fibers of paper against which color has bled as if memory. Some refer to it as the heart of the Sichuan Museum Zhang Daqian Gallery, and I think that’s about right. This is a space that hums with quiet confidence — nothing shouts here, but every brushstroke does linger.

In their TripAdvisor reviews, that there’s “serene lighting” and “the curation is on a museum level,” which is funny since this is exactly what you feel. The glass isn’t glaring; the air appears to be holding its breath. For those familiar with the Chengdu art world, this room seems an unadvertised connection to a Sichuan connection: a reminder that modern Sichuan painting didn’t spring out of nowhere — it came from hands like Zhang’s, both steady and restless. When you emerge, the daylight is crisper, almost blue. It’s hard not to look back one more time on your way out.

Ethnic Minorities & Tibetan Buddhism Section

Upstairs, the tone changes. The smell changes — wood polish tinged with the scent of distant incense — and the colors become brighter: reds, saffron, turquoise thread. At Here, Tibetan art of Sichuan Museum is mingled with embroidery and silver ornaments from Yi, Qiang and Tibetan nad Qiang people’s. The fabrics shine with handwoven geometry; a Tang-style bronze Buddha stands alone in soft yellow light, face worn but kind. The room is alive but hushed; visitors lower their voices without knowing why.

You may discern the thumbprints in the clay of a statue, or frayed edges of an old monk’s robe. That’s the intimacy of Sichuan Museum ethnic minorities collections — they articulate faith through touch, through artifacts that are still imprinted with evidence of those who held them. It is cooler, and the light waits. “This bit feels spiritual even if you're not religious,” per TripAdvisor — and that’s exactly the idea. Whether you nod, linger or merely inhale the silence, this part calls for stillness.

On the far wall, another chamber shimmers faintly gold — painted mandalas and ritual tools glittering in filtered light. It’s less exhibit, more heartbeat. This exhibit among all of the Sichuan Museum’s presentations of Tibetan art hushes it all. And when you emerge back into the stairwell, this time after a half hour or so, it seems incongruous to let the sound of that city in — as though you have accidentally walked out of another era.

Practical Visitor Guide: Tickets, Transport & Hidden Pitfalls

- Souvenir of Sichuan Museum

- Exhibits in Sichuan Museum

Getting There Without Losing Your Way

As for how to reach Sichuan Museum, the answer seems straightforward — but in Chengdu, simplicity still contains an element of wonder. The metro is the most straightforward: Line 2, in the direction of Xipu, and then get out at Culture Park Station, Exit B. It’s about a 10-minute walk from there to the site: just follow signs that still say “四川博物馆 Sichuan Bowuguan.” Except for the time I got off a stop too early, at People’s Park, and I found myself in front of a labyrinth of teahouses. A red-vested volunteer saw my bewildered face, laughed and gestured the way in broken English. That’s Chengdu: slow, helpful, occasionally lost.

You can also bus — routes 35, 58, 82 and 151 get you close to the monastery — or call a Didi cab; one from downtown Tianfu Square should be about ¥12–15. A good 15-minute walk from Du Fu Thatched Cottage through Huanhuaxi Park, shrubby and quiet if it’s not raining. Most locals advise taking Chengdu’s Metro to Sichuan Museum specifically because of the parking hassle; the small lot fills up quickly, especially on weekends.

Tickets & Entry Tips for Visitors from Overseas

First, the good news: Tickets to Sichuan Museum are free. You just need to register. Out-of-town visitors can scan the QR code at the entrance or make reservations in advance on the official site. On the Web you enter your passport number in lieu of a Chinese ID. Slots release three days ahead, and they’re whisked away fast on holidays. Registration in person is constructively feasible too, assuming it isn’t too crowded: Bring your actual passport — photos don’t count.

Security screening is done twice: once at the main door and then in proximity to lockers. So if you want to bring an apple in a plastic bag for the two-hour journey, that’s fine, but keep your lighter and snacks at home. Bags are X-rayed; the guards are courteous and stern. When it comes to the museum’s own word, you should be in line and “ready 30 minutes before closing,” but New Yorkers have said that 4:30 p.m. is more like the last comfortable entry. If you’re thinking is the Chengdu Museum free, the answer’s yes — but this one somehow feels simpler, less crowded and more chilled out. Photo Keep your booking QR code easily accessible; an image on a phone can falter in the face of glare.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Most reviews of the Sichuan Museum are effusive, but there are a few patterns that recur. The first mistake: Mailing it in — as in, forgetting to book online during a holiday. You will see them standing outside, looking despondent until you realise this is were standby pax await fruitlessly. Second: ignoring Monday closures. The museum is closed every Monday except national holidays, and even locals forget that. Third: You only visit the ground floor. Many people run through the bronzes, miss the Zhang Daqian gallery upstairs and leave saying “it’s smaller than I thought”.

If you want to navigate local customs as smoothly as you move through the galleries, you might enjoy learning a few essential dos and don’ts from Chinese Etiquette: Essential Tips for Foreign Travelers Visiting China.

Here’s how to avoid those traps. Book two days in advance, arrive before 10 a.m. and work from the top floor down — cooler, emptier. Bring ID, water, and patience. TripAdvisor reviews note that weekday afternoons are a fine time to get attuned: Families thin out, and the volunteer crooners have time to chat. That’s when you start to hear the stories behind those artifacts. Go slow; that’s the ultimate Sichuan Museum visiting tip.

FAQs about Sichuan Museum

Q: Is the Sichuan Museum free to enter?

Yes, Sichuan Museum Chengdu has free entry however you need to register before going in. Foreign visitors can book on the official site with a passport or sign up at the gate if there is space. Weekend reservations go quickly, so target early mornings. Good security checks need to be done, lockers available free of charge. On the digital front, have your code on tap; it can be scanned at the entrance before you enter the halls.

Q: What is the best time to visit Sichuan Museum to avoid crowds?

Friday-afternoon, the after-work week picnic hour (about 3:00 p.m.) is said to be a chill time by locals. School tours have ended by then, and the Sichuan Museum Chengdu air is cooler. Steer clear of Saturdays and public holidays, when family groups throng the pottery-and-bronze galleries. Reviewers on TripAdvisor say early mornings are relatively quiet too, but if you want time for sketching or snapping photos of the light filtering through the windows, go after lunch.

Q: How long does it take to see all the exhibits?

Most visitors get around in two hours, but dig the art, and you could stretch this to four. Sichuan Museum is actually bigger than it initially seems, boasting 14 galleries and over 300,000 relics. If you go too quickly, you will miss things — the little patterns on Han bricks or brushstrokes in a Zhang Daqian painting. Take your time: an hour a floor is doable and still leaves room for a coffee break on the ground floor.

Q: Can I take photos inside Sichuan Museum?

Yes, photography is generally permitted in the halls (special exhibitions are exceptions). Just turn off your flash; guards take visitors to task immediately. Walking through the Sichuan Museum’s Chengdu painting galleries, lights are dimmed to protect pigments, so be sure to have a steady hand. TripAdvisor reviewers advise coming in on sunny afternoons for natural light. You can even selfie in the lobby — it’s sprawling, bright and brimming with organic bamboo textures.

Q: Is there an English audio guide available?

For an additional fee, you can rent or buy an English guide near the entrance; bilingual captions are available in front of certain major relics after scanning a QR code. “Some of the translations are better than others, but they give you enough to follow along with each hall’s story,” says some travelers. If you like context, consider downloading the free “Chengdu Culture” app — it’s connected to the Sichuan Museum Chengdu audio channels and comes with brief background clips about bronze work and Han pottery.

Q: What is the difference between Chengdu Museum and Sichuan Museum?

Downtown, Chengdu Museum beside Tianfu Square portrays urban history and has interactive displays. By contrast, Sichuan Museum is located close to Huanhuaxi Park, and has an older, more sedate feel as well a far larger collection of regional artifacts. And if you love archaeology and classical art, Sichuan all the way. If your tastes run toward digital displays and modern art, Chengdu Museum is more up your alley. Visit both in a single day (many visitors do) to get a complete picture of the city’s culture.

Q: What other top museums should I see in Chengdu?

From there, move on to the Jinsha Site Museum, where golden masks and ancient ivory carvings from 3,000 years ago gleam beneath dim amber lighting. Then check out the Sichuan Science and Technology Museum, a kid-friendly favorite. If food heritage is your jam, then visit the Sichuan Cuisine Museum in Pixian for a literal taste of history – you can even join a cooking demonstration. Together, these are the best museums in Chengdu circuit.

Q: Is there food or coffee inside the museum?

Yes, there’s a tiny café close to the first floor souvenir shop dispensing lattes and local-style nibbles for around ¥25–35. No eating in galleries at the Sichuan Museum Chengdu complex, but the outdoor benches overlook bamboo groves; these are great for a rest between exhibits. If you’re looking for a real Chengdu flavor, some locals suggest picking up noodles at “Lao Ma Tou,” a five-minute walk on, rather than the museum café.