Most folks think of the Great Wall or Terracotta Army when China comes up. Fair. They’re bold, photogenic, easy to Google. But the Grand Canal? That’s a different story. It’s not loud. It doesn’t shout. You might not even notice it at first. But it’s there—running quietly for more than 2,000 years, through cities like Hangzhou and Suzhou, threading the whole country together like stitches in an old robe that somehow still fits.

And yeah, it’s still in use. That’s the part that got me. Locals bike beside it. Grain barges drift past like nothing’s changed since the Qing Dynasty. There’s something deeply human about that. Something that doesn’t need fanfare to feel important.

If the quieter corners of history interest you more than tourist-packed landmarks, we’ve also got a full China World Heritage Sites Travel Guide—it might just pull you into a rabbit hole you didn’t expect.

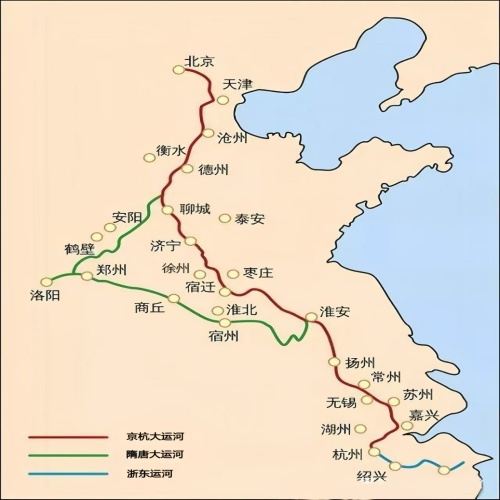

China Grand Canal Route

What Makes the Grand Canal One of China’s Most Important Heritage Sites?

A Man-Made Marvel That’s Still Flowing Today

The first time I stood by the canal—somewhere in Yangzhou, near Dongguan Street—I thought: this can’t be it, right? It looked... peaceful. Too peaceful. No wide arches, no dramatic cliffs. Just still water, a stone bridge or two, and a couple of aunties hanging laundry by the bank.

But here’s the thing—it is it. That’s the Grand Canal. Over 2,500 years old, still flowing, still doing its thing. It predates the Roman aqueducts. It saw dynasties rise, fall, and rise again. And while parts have faded, others have evolved. The Hangzhou section feels almost meditative; up north in Tongzhou, Beijing, it’s more industrial, more matter-of-fact.

And yet, it all connects. You don’t just look at the Grand Canal—you follow it. Maybe by foot, maybe by train, maybe by accident. But somewhere along the way, it hits you. This isn’t just a feat of engineering. It’s a long, meandering memory. One that hasn’t stopped moving.

Not Just a Canal—A Mirror of Chinese Civilization

If someone told you that a canal could explain China, you'd probably raise an eyebrow. I mean, really? A ditch with water? But walk a few kilometers along the Grand Canal—maybe somewhere between Suzhou and Wuxi—and it starts to make weird sense. It’s not just a water route. It’s like a slow-moving scroll of Chinese civilization, unrolling as you go.

Back in the Tang and Song dynasties, it wasn’t just grain heading north to emperors. Boats carried books, tea, gossip, dialects—entire worldviews. Scholars floated downstream, chatting about poems and policy. Opera troupes packed into wooden barges, performing in dockside towns. This water didn’t just feed cities. It transmitted culture, the same way ink flows on paper.

And then there’s the way it’s built. Ever notice how the canal isn’t straight? It meanders, curves with the land, like someone tracing their finger across silk. That wasn’t an accident. Chinese planners—especially during the classical periods—weren’t about forcing symmetry. They designed around the idea of shun qi zi ran (顺其自然): follow the flow. Kind of like Confucius meets fluid dynamics. Compared to the brutal logic of Roman roads, the canal feels... poetic.

You feel this most in towns that grew up along the banks. Suzhou didn’t become a hub for poets by accident. Hangzhou’s silk boom? That’s water economy 101. And Yangzhou? Still one of the best spots to sip tieguanyin in a canal-side teahouse while someone nearby plays guqin. You’re not just watching history—you’re sitting in it. Quietly. Maybe that’s the best part.

Why Travelers Still Follow Its Path Today

So, why are travelers still drawn to the Grand Canal in 2025? It’s not about the thrill, like Zhangjiajie’s glass bridge. And it’s definitely not your usual Instagram spot. But if you're into slow travel, this is gold. You hop on a bike in Wuxi or take a canal boat ride in Suzhou (usually around 40–60 RMB, roughly $6–9), and for a moment, modern China blurs.

What’s nice is that many parts of the Grand Canal have been revitalized. I stayed in one near Tongli that had QR menus and staff who spoke passable English—definitely not a given in rural spots. You’ll notice a mix of UNESCO signage, food stalls, and actual locals who still use the canal like it’s 1600.

Some places, like Hangzhou’s Grand Canal Museum (free entry, with English guides available), offer interactive displays that help you grasp its legacy. Others, like Zhenjiang or Jiaxing, let you see ancient canal locks still functioning. You’ll find tourists, sure, but also morning joggers, old men fishing, and women selling lotus root soup. It’s the real deal, just with a few more selfie sticks.

Grand Canal Museum

How Was the Grand Canal Built—and Who Paid the Price?

From Small Waterways to Imperial Vision

It’s easy to forget, but the Grand Canal didn’t start as one big idea. It grew slowly, piece by piece. Early sections date back to the 5th century BCE, used for local farming transport. Picture ancient villagers moving grain by wooden rafts—nothing fancy. But then emperors got involved. By the time of the Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE), things scaled up fast. Emperor Yangdi wanted one single canal to unify north and south China, both politically and logistically. That’s when it went from regional project to imperial obsession.

Now, imagine trying to connect rivers with different elevations, across marshes and mountains, without modern tools. No GPS, no cranes, just manual labor and rough math. The Sui government conscripted millions of peasants—some records say 5 million—to dig channels by hand. They didn’t just move dirt; they shaped China’s map. That image alone is staggering. You walk by a canal bank in Yangzhou or Jining today, and you’re literally tracing lines that were carved by exhausted human hands.

Foreigners sometimes compare it to the Panama Canal or Roman aqueducts. But here’s the kicker: this wasn’t done for trade alone. The Grand Canal was also about power projection. Grain meant stability, and stability meant loyalty. So, in building it, the emperors weren’t just moving rice—they were binding a fractured country with water. That’s the kind of logic you can only get from a very old, very ambitious civilization.

Forced Labor and Imperial Glory—A Price Paid in Blood

You don’t usually hear this part. When people talk about the Grand Canal, they mention engineering feats or poetic views—but not the bodies. During the Sui Dynasty, when construction peaked, it wasn’t cranes or contracts moving the earth. It was people—peasants yanked from farms, marched across counties, digging by hand through brutal heat and freezing winds. Some died from exhaustion. Others from disease. Many were simply never seen again.

In places like Linqing or parts of Shandong, you can still hear echoes of that pain. Folk songs—soft, almost murmured—pass down stories of men who left and didn’t return. It’s strange. You walk by the water today, and everything feels calm, efficient, even a little proud. But under that surface is another story—one of forced loyalty, imperial ambition, and the human cost of building something "great."

Still, that sacrifice… it did fuel empires. The Grand Canal kept cities like Chang’an and Kaifeng alive. It fed marketplaces, moved armies, and made imperial life possible. So you’re not just looking at history—you’re looking at a trade-off. Something grand, yes, but heavy. And when you stand by that water now—especially where it’s quiet—you might feel it. Not sadness, exactly. More like a weight you didn’t expect to carry.

How Did Later Dynasties Keep It Alive?

Most ancient megaprojects fade with time. But somehow, the Grand Canal kept moving, century after century. It didn’t just survive—it shapeshifted. The Yuan Dynasty, with their capital up in Dadu (what’s now Beijing), needed grain—fast. So, they rerouted sections of the canal northward, even pushing through mountain terrain. On paper, it sounds a bit reckless. In reality? It kept their empire fed.

Then came the Ming and Qing. These dynasties didn’t just maintain the canal—they institutionalized it. Full-time hydraulic engineers were stationed across provinces. Locks were redesigned, and entire bureaucracies formed around moving grain. It got weirdly specific, like each province had its own poetry-infused shipping department. Some of the records read like Confucian logistics manuals—rice quotas, water depth logs, even “acceptable boat behavior.” It wasn’t just a waterway anymore. It was statecraft.

Even when trains and highways entered the game, they didn’t totally kill it. In the 20th century, parts of the canal were dredged and re-activated. Then came 2017—the Grand Canal Cultural Belt initiative. China started pumping money into restoration, museums, and yes, boat tourism. Now? You can be in Hangzhou, sipping tea on a barge with onboard WiFi, gliding past centuries-old bridges. It’s surreal. But it’s also very China—where past and present somehow hold hands without looking awkward.

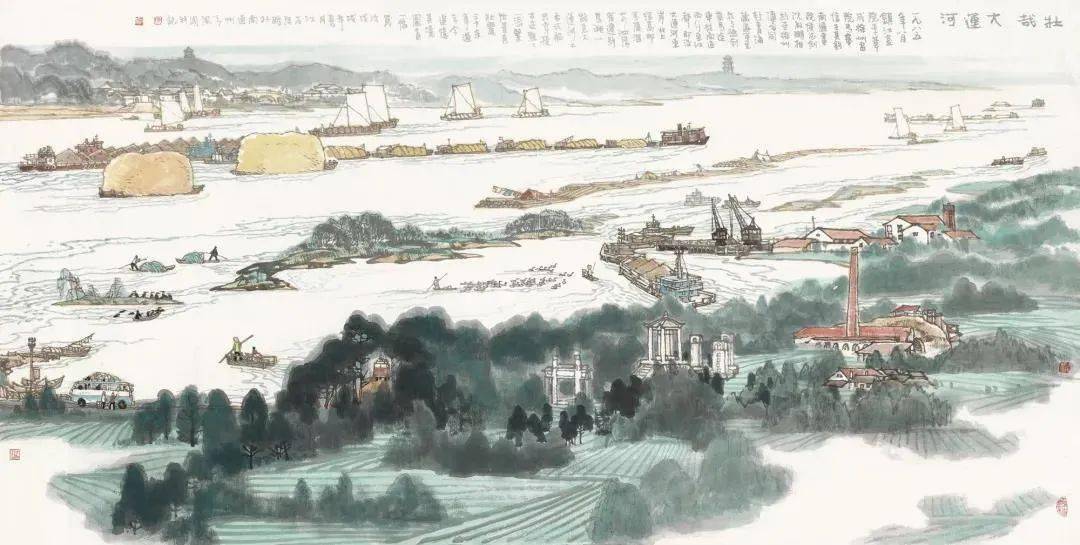

Ancient Grand Canal

Where Can You Still See and Touch the Grand Canal Today?

The Most Beautiful Sections to Visit as a Tourist

If someone told me the Grand Canal was just a ditch, I’d probably assume they never saw Hangzhou’s Gongchen Bridge at 6 a.m.—before the scooters, before the tour groups. There’s this moment when the sun spills gold across the water, and everything—tai chi, laundry lines, the quiet shuffle of early walkers—feels frozen in soft motion. It’s not grand like Versailles, but it breathes.

This part of Hangzhou still gives you that layered feel. You’ve got stone docks from the Qing dynasty, next to a café with oat milk lattes and canal views. The boat rides? Surprisingly decent. A little kitsch maybe, but you pass scenes that feel lifted from some ancient scroll—except, you know, there’s Wi-Fi now.

Yangzhou’s canal feels different. Less showy, more poetic. Near Slender West Lake, the water slows and the trees start leaning in like they’re eavesdropping. You’ll see bilingual plaques that actually make sense, and if you’re lucky, a local guide who doesn’t just repeat facts but tells you which emperor nearly drowned nearby. Suzhou? That’s where it gets casual. Locals eating noodles on the banks, old men fixing bikes next to tour boats—it’s lived-in, and that makes it better.

· Hangzhou Gongchen Bridge cruise: 60 RMB (≈8 USD)

· Yangzhou Grand Canal section access: Free, especially near Slender West Lake

· Suzhou Shantang Street cruise: 45–55 RMB, depending on boat type

Beyond the Water—Cultural Treasures Along the Canal

You go expecting boats, and somehow end up at an opera. That’s the Grand Canal effect. In Huai’an, I stumbled on a Kunqu stage lit by paper lanterns. No warning, no fancy signs—just a few rows of stools and an old lady handing out warm tea. The performance? Barely miked, completely mesmerizing. It wasn’t for tourists. It just was.

Cangzhou’s spring puppet festival was louder—shadow puppets flickering across silk screens, families cheering at every move. You wouldn’t think something so delicate could fill a plaza, but there it was. Near the docks, no less. That blending of space—cargo routes and culture corners—is kind of what makes the canal special. It carries more than water.

Then there’s the Grand Canal Museum in Yangzhou. Interactive stuff, real models, English everywhere—it actually respects your brain. You can stand inside a recreated Song grain boat, press a button, and watch how tax ledgers were calculated centuries ago. Also: free entry, if you’ve got your passport.

· Yangzhou China Grand Canal Museum: Free, closed Mondays, bring passport

· Huai’an Kunqu Opera near Qingjiangpu: 80–120 RMB, evening shows

· Cangzhou Puppet Festival: Free, held early April

Can You Cruise the Grand Canal Like Ancient Officials Did?

Short answer? Kind of. You won’t be wearing robes or dodging pirates, but the vibe is there. I once took a ride in Suzhou where the guide dressed like a Song dynasty tax collector and told stories about canal smugglers between sips of chrysanthemum tea. A little over the top? Sure. But it weirdly worked.

In Hangzhou, the Wulinmen to Gongchen stretch runs past old locks and stone granaries. Not tourist-trap polished—more like, "oh wow, that wall really is from 1100 AD" kind of real. And most cruises now offer some kind of English explanation—either via audio guide or laminated cards with surprisingly poetic translations.

You don’t usually need to book ahead unless it’s a weekend or a national holiday. But hotel staff, especially at foreign-friendly places like JW Marriott Hangzhou or Crowne Plaza Suzhou, can hook you up with tickets. Some even bundle boat tours into the room package. Not a bad deal if you’re jetlagged and want a smooth start.

· Hangzhou boat (Wulinmen–Gongchen): 50 RMB, buy onsite or ask your hotel

· Suzhou heritage boat: 65 RMB, includes guide narration

· Foreigner-friendly stay: JW Marriott Hangzhou – accepts international passports

- Hangzhou Gongchen Bridge

- Yangzhou Slender West Lake

- Crowne Plaza Suzhou

What’s the Future of the Grand Canal in Modern China?

Reviving the Past with Smart Tourism and City Planning

It’s kind of wild how the Grand Canal—this massive, old-school feat of labor and mud—has found its way into app stores. In Hangzhou, for instance, I saw someone scan a QR sign by the water and suddenly their phone was playing an AR story with boats and ancient poets. Not TikTok stuff—like, actual Confucian poetry floating across the screen. Totally unexpected.

Local governments have really leaned into this “cultural belt” branding. And it’s not just slogans. You now get canal-front hostels with English signs, old warehouses turned into cafés, and even rental bikes with historical route overlays. A place like Suzhou doesn’t just want to show off its past—it wants to frame it in WiFi. Which… sounds weird, but somehow works.

The coolest bit? Each city along the canal kind of does its own remix. Yangzhou might brag about ancient salt merchants. Suzhou goes for elegance and silk. Wuxi’s got museums. That mix keeps things fresh. No two stretches feel the same, and honestly, that’s what makes it worth tracing.

From Industrial Waterway to Ecological Lifeline

There was a time—not long ago—when parts of this canal stank. Like, literal factory sludge kind of bad. Some stretches near Huai’an looked more like oily drainage than heritage. I remember asking someone, “Wait, that’s the Grand Canal?” and they just shrugged.

But that’s changed, fast. Since the UNESCO stamp in 2014, the clean-up has been serious. I passed through Wuxi last spring and saw lotus ponds where industrial plants used to belch smoke. Kids were running around birdwatching zones. Even egrets showed up. I mean, egrets! Along a canal once written off as dead.

Sure, it’s not perfect. You won’t be sipping canal water anytime soon. But planners now talk about a “drinkable, swimmable, livable” waterway. Maybe that’s ambitious, or maybe it’s China doing what it does best—turning massive infrastructure into symbols. And this time, it’s not about empire. It’s about breathing room.

Is the Grand Canal Becoming a Global Story?

I didn’t expect to hear about the Grand Canal while browsing an exhibit in Vienna, but there it was—Tang dynasty trade routes, model barges, silk scrolls. Turns out, China’s been slowly exporting this piece of heritage. Through cultural centers, traveling shows, even museum partnerships, the canal is now part of the “soft power” playbook.

There are even international tour groups now—yeah, really. A few agencies run canal-themed routes from Beijing to Hangzhou, mixing food, history, and architecture, all stitched together by the water. Some are surprisingly well-done, with trained guides who don’t just rattle off facts but actually explain, say, how the Ming lock system worked. Not massive crowds yet, but it’s gaining attention.

So, global icon? Maybe not quite. But it’s getting there. The way locals now treat the canal—with signage, storytelling, preservation—it feels like a quiet confidence. Like they know this isn’t just China’s past. It might just be part of its future narrative too.

Sucheng District, Suqian City: Creating a "waste-free canal"

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Is the Grand Canal in China the same as the one in Venice?

Not even close. They just happen to share the same name in English. China’s Grand Canal—locals call it the Jing-Hang Da Yunhe—runs from Beijing to Hangzhou. That’s over 1,700 kilometers of human-dug waterway, with some parts dating back to the 5th century BC. Venice? Gorgeous, sure, but it’s a short natural canal in a floating city, famous for gondolas and Renaissance buildings. If you searched “Grand Canal Venice” and saw something about Chinese barges—you didn’t click wrong. Just landed on the older, longer, more empire-powered version.

Q: What’s the difference between the Grand Canal in China and the one in Dublin?

A bit like comparing a hiking trail to a cross-country freight line. Dublin’s canal is cozy—people walk dogs there, sip coffee, maybe spot a narrowboat drifting by. It’s lovely in a laid-back way. China’s Grand Canal? It once kept an entire dynasty running. Grain, troops, taxes—all moved along that water. It’s infrastructure, not a stroll. Think imperial logistics rather than leisure paddling. So yeah, they’re both canals. But one’s a nice walk and the other once fed an empire.

Q: Are there luxury hotels or “Grand Canal suites” along the Chinese Grand Canal?

Not in the Vegas way, no. You won’t find canal-front casinos or anything glittery. But if you want a beautiful old building turned into a boutique hotel, with red lanterns and willow trees right outside your window—then yes. Suzhou has places like that, especially near Pingjiang Road. So does Hangzhou, around Gongchen Bridge. Rooms go for around 300–800 RMB per night, depending on season and location. It’s not flashy. But there’s charm in hearing water slap the stones while sipping tea in a Ming-style courtyard.

Q: Can I visit the Grand Canal of China at famous landmarks like “the church of la salute”?

That search’ll send you straight to Venice. But here’s the thing—China’s canal has its own spiritual stops, just less Instagrammed. In Hangzhou, Gongchen Bridge sits right by old temples. In Yangzhou, Daming Temple is literally steps from the water. Zhenjiang’s Jinshan Temple rises from an island mid-river, steeped in legends. No marble domes, no mosaics—but you’ll get incense, carved wood, and history that breathes. If you’re looking for awe, just give it a different lens.

Q: Where should I start if I want to explore the Grand Canal in China?

Depends on what you’re after. If you like ease and decent coffee, Hangzhou’s a safe bet—good infrastructure, plenty of signage, and yes, boat rides near Gongchen Bridge. If you're chasing history, go north a bit to Yangzhou. It’s where the old grain routes met the empire’s tax machine. Want the full experience? Try tracing the canal top to bottom—Beijing to Hangzhou. The high-speed rail runs nearly parallel, so you can skip the dull bits. But honestly, don’t expect postcard scenes the whole way. Some parts feel industrial, others feel like a dream.

Q: Can I walk or bike along the Grand Canal in China?

Yep—and you absolutely should, at least for a few kilometers. In cities like Hangzhou, Suzhou, and Yangzhou, the canal-side has been turned into greenways. You’ll pass locals playing cards, see old men fishing with bamboo poles, and hear the occasional vendor calling out about fried dough. It’s not a performance. It’s just… life. Slowly moving forward.

In Hangzhou, the stretch near Gongchen Bridge has clean paths and cheap bike rentals—under 20 RMB per hour. Suzhou’s Pingjiang Road runs beside narrow canal arms with arched stone bridges and tea shops that feel untouched by time. You don’t need a plan—just follow the water and see where it takes you.

But heads-up: not all 1,700 km are this charming. North of Jiangsu? It gets industrial real quick. The southern parts—especially in Jiangsu and Zhejiang—are where the canal still whispers.