If you think China’s World Heritage Sites are just pretty backdrops for photos, think again. These places don’t just sit there—they hum, move, cook, chant, and occasionally argue with the present. You might sip tea where emperors once planned dynasties, or hear a grandma in a 700-year-old village singing the same lullaby her great-grandmother did. In China, heritage isn’t sealed in glass—it’s part of daily life.

With 57 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, China offers more than grand monuments. It gives you moments—embroidering silk in Suzhou, walking through misty rice terraces in Yunnan, lighting a lantern in Pingyao. This article shows you where culture isn’t just seen, but felt—through taste, music, story, and sometimes even a shared meal. Ready to travel a little deeper?

What Makes China’s World Heritage Sites Different From Anywhere Else?

Forbidden City

It’s Not Just Stone—It’s Still Breathing

Some world heritage sites feel like time capsules. China world heritage sites feel like people never left. You don’t just see monuments—you hear chopsticks clicking, smell incense trails, and watch locals walk straight through thousand-year-old gates like it’s any Tuesday.

When I visited the Summer Palace in Beijing, I expected a quiet walk and some photos. What I got instead was a flute melody drifting from a nearby boat, a man feeding fish with bits of his steamed bun, and a kid reciting poetry under a painted corridor. This wasn’t staged. This was someone’s weekend routine—in a UNESCO site.

The difference shows in small things. In most cities, ruins are roped off. In China, a granny might sit on a Ming Dynasty stone bench to peel her oranges. And surprisingly, the infrastructure is ready for outsiders. Sites like the Forbidden City, Pingyao, and Leshan now feature English signage, mobile guides, and transport links with bilingual service. A train from Xi’an to Luoyang Longmen Grottoes costs under 120 RMB, with helpful staff who can point you in the right direction even if your Mandarin is rusty. These places don’t just survive. They function.

A Story Carved in Layers: Culture, Belief, and Daily Life

You don’t just visit China world heritage sites, you step into centuries stacked like old books. Think about a place like Mount Wudang. You see temples and stairs—but you also hear monks humming at dawn, see locals burning paper money, and watch teens trying slow Tai Chi under peach trees. The architecture? Sure, it’s stunning. But it’s the people that make the story stick.

Everything overlaps. A building may be imperial, but a festival may be Daoist, while food sold nearby traces back to a family recipe from 500 years ago. At West Lake in Hangzhou, I watched a couple dressed in hanfu pose under a willow while behind them, an old man whispered Tang poetry to his grandson. It's like history's greatest hits playing at the same time—and no one minds the mashup.

Western visitors sometimes ask, “Is this part real?” The answer is always both yes and no. China doesn’t separate legend from heritage. The myths, the smells, the rituals—they all stay in the room. And when you leave, they might follow you home, in the best way possible.

From Intangible to Monumental: The Dual Heritage System

What truly sets China world heritage sites apart is how the country treats stories and skills as equal to buildings. You can see the Great Wall in the morning and, by evening, be hand-folding dumplings in a nearby village courtyard that hasn’t changed since the Qing Dynasty. One’s on the UNESCO list. The other? Not yet—but it should be.

In places like Suzhou, it’s not just about the gardens. It’s about the women inside them, stitching Su embroidery with threads so thin they split hairs. In Fujian, yes, the tulou earthen homes are heritage-listed. But what matters more is that families still live inside them—three, four generations under one roof, cooking, laughing, arguing. You’re not just walking through culture. You’re dodging soup steam and hearing bedtime stories too.

UNESCO’s got the stats: China holds the second-highest number of heritage sites globally, only behind Italy. But when you factor in intangible cultural heritage, China leads the world. That means music, medicine, festivals, crafts—living knowledge. And tourists aren’t shut out. Many sites now offer hands-on classes for under 100 RMB, from kite-making in Weifang to calligraphy in Xi’an. Some hotels, like the Garden Hotel Suzhou, even bundle cultural activities with your stay. So yes, the walls are old. But the hands that built them? Their rhythm is still here.

Can You Still Experience These Sites Like Locals Did Centuries Ago?

Morning Prayers in Lijiang, Followed by a Naxi Song

Lijiang isn’t some polished fairytale town. It’s old, yes—but not museum-old. When I stayed at a guesthouse inside the old town, the wooden floors creaked every time someone walked past. At dawn, I woke to the sound of soft chanting. A Naxi elder stood in the alley, bowing toward the mountains. Behind him, the sky turned blue slowly, like someone pouring ink into water.

That’s the kind of moment China world heritage sites can give you when they’re still lived in. The Naxi people, who once ran trade routes along the Tea Horse Road, still practice their rituals here. I wandered into a courtyard later that day and heard traditional music—not recorded, but played by hand. One man had been performing the same piece since he was 17. “My father played it too,” he told me. “Now I play it for my grandson.” It wasn’t a show. It was life.

Getting there is easier than expected. Flights to Lijiang Sanyi Airport arrive daily from Chengdu or Kunming. From the airport, it’s a short taxi ride to the old town. Hotels like The Bivou Lijiang or Intercontinental Lijiang Ancient Town welcome foreign guests and provide English-speaking staff. A stay ranges from 300–600 RMB per night, depending on season. And don’t worry—signs in the old town come in both Chinese and English, and locals are used to visitors. It’s not about getting everything perfect. It’s about slowing down enough to notice what hasn’t changed.

Learning Su Embroidery at a Humble Pavilion in Suzhou

Suzhou gardens are delicate—carefully composed like scroll paintings. But inside one quiet pavilion, I found something more intimate: a woman embroidering a crane, stitch by stitch. She didn’t look up. Her fingers moved like they were dancing. I sat beside her for nearly an hour, just listening to silk thread rub against cloth.

You might visit China world heritage sites expecting architecture. But in Suzhou, you get gestures passed down through generations. Su embroidery is one of China’s oldest craft traditions. In places like Zhenhu Silk Street, visitors can take part in hands-on classes. I joined a half-day session. My hands were clumsy. My stitches were crooked. But the teacher laughed, adjusted my frame, and showed me again. She didn’t say much. Just, “Keep going.” And I did.

Suzhou is only 25 minutes by high-speed train from Shanghai, with tickets as low as 40 RMB. Once in the city, garden entries range from 30–90 RMB. For a deeper cultural stay, try Tonino Lamborghini Hotel Suzhou—they accept international guests, and the staff can help book workshops. Even if you don’t sew perfectly, there’s something calming about touching a tradition that hasn’t rushed in 600 years. You won’t leave with a masterpiece. But maybe that’s not the point.

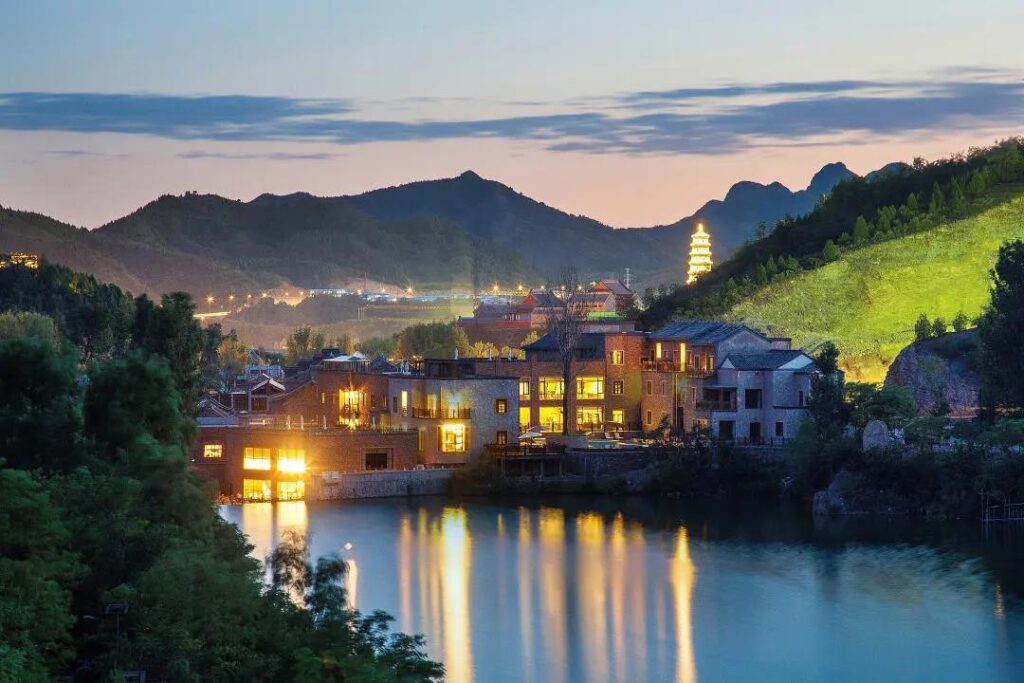

Behind the Great Wall: Cooking with Locals in Gubei

You’ve seen the photos—majestic, endless wall slicing through mountains. But what’s behind it? In Gubei Water Town, just outside the Simatai section of the Great Wall, I found something unexpected: a dumpling class in a tiled courtyard kitchen. A middle-aged woman named Zhao waved me in after I asked what smelled so good. An hour later, I was making fillings while she explained her grandmother’s garlic trick.

This is the surprise of China world heritage sites—they’re not just built from stone but from memory. Simatai is a stunning part of the wall, open for both day and night hikes. But spend the night in Gubei, and you’ll find people willing to share not just views, but stories. During Dragon Boat Festival, the town is full of zongzi vendors. Each family’s version is different—pork belly, red bean, salted egg yolk—all wrapped in leaves, tied with twine, cooked in giant pots.

From Beijing, Gubei is about 2.5 hours by bus or car. Entry to the water town is around 140 RMB, with add-ons for the Simatai Wall hike or boat ride. Stay at places like Wuzhen Inn or Gubei Watertown Hotel, both of which accommodate foreign travelers. And yes, they’ll help you find the dumpling class if you ask nicely. In the end, I left Gubei with sore hands, flour on my jeans, and more warmth than I expected. That night on the wall, under the stars, I couldn’t stop smiling.

- Suzhou Gardens

- Gushuibei Town

What Are the 7 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Beijing?

You hear “Beijing” and probably think Forbidden City, maybe the Great Wall if you’re a bit more into it—but there’s more, way more, tucked between subway lines and winding highways. I didn’t expect to find seven full-on UNESCO world heritage sites here, packed into one metro-accessible city. Some of them feel legendary—like, you stand there and think, “How did they even build this?” Others, honestly, you might drive past without noticing unless someone points it out (Zhoukoudian was one of those for me—looked like a hillside, turns out it's 700,000 years old).

The thing is, not all of these places hit the same way. The Summer Palace? Absolute poetry, especially if you catch it near sunset with someone playing an erhu on the bridge. The Ming Tombs though—I mean, if you don't take a guided tour or read up first, you might just feel like you're walking through a quiet forest. And speaking of guides, not every site is tourist-friendly in the “press one for English” sense. Some have slick apps and signage, others… well, bring a translation app or a patient local friend.

So if you’re trying to figure out which ones are worth the subway ride (or Didi fare), this quick breakdown should help. I’ve thrown in prices, highlights, and whether you’ll get stuck staring at a plaque in Chinese, wondering what dynasty you're supposed to be impressed by. Some are unmissable. Some—you might just skip depending on your mood, and honestly? That’s fair.

| Site | 中文名称 | Heritage Type | Highlights | Entrance Fee (Approx.) | English Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Great Wall (Badaling/Mutianyu) | 长城(八达岭/慕田峪) | Cultural | Iconic defense wall, scenic hikes | ¥40–60 RMB | Yes (signage + guides) |

| The Forbidden City | 故宫博物院 | Cultural | Imperial palace, over 9,000 rooms | ¥60 RMB (off-season)¥80 RMB (peak) | Yes (audio guide + app) |

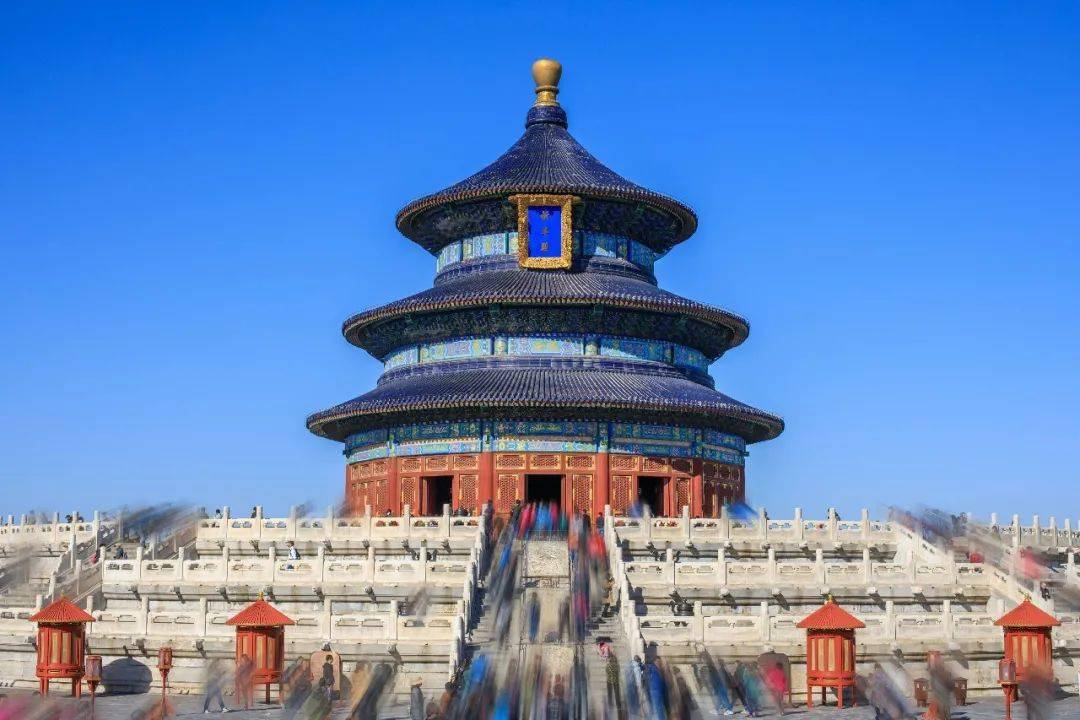

| The Temple of Heaven | 天坛 | Cultural | Circular altar, ancient ceremonies | ¥34 RMB (through ticket) | Yes (some signs + guidebooks) |

| The Summer Palace | 颐和园 | Cultural | Lakeside retreat, Long Corridor | ¥30–60 RMB (depends on combos) | Yes (audio + map app) |

| The Ming Tombs | 明十三陵 | Cultural | Underground palaces of 13 emperors | ¥30–60 RMB per tomb | Partial (some bilingual panels) |

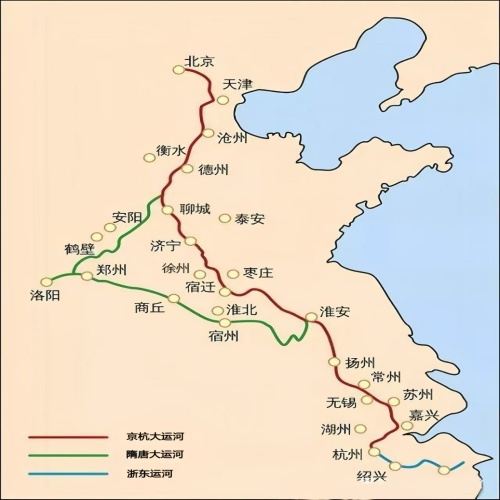

| The Grand Canal (Tongzhou Section) | 大运河(通州段) | Mixed (Cultural/Natural) | Historic water route, boat tours | Free or ¥20–50 RMB for cruises | Yes (boat guides, some QR displays) |

| Zhoukoudian Peking Man Site | 周口店猿人遗址 | Cultural | Early human fossils, cave system | ¥30 RMB | Basic English signage |

Notes:

All these sites are officially listed under UNESCO and contribute to China world heritage sites count.

Most major sites (like the Great Wall and Forbidden City) support foreign visitors with multilingual signs or audio guides.

For in-depth touring, booking via Ctrip or Trip.com ensures English services and online ticket access.

Hotels near these attractions—like Beijing Hotel NUO or The Opposite House—welcome foreigners and offer concierge translation help.

- Temple of Heaven

- Forbidden City

What Can You Actually Do There—Beyond Taking Photos?

Join a Shadow Puppet Workshop in Xi’an

Xi’an is famous for its warriors, but what caught me off guard was the shadows. Not the literal ones—but the kind that dance across silk screens in tiny puppet theaters. Down a narrow alley near the Drum Tower, I found a studio where a sixth-generation shadow puppet master slices donkey hide into delicate patterns, dyes them with crushed minerals, and brings them to life under candlelight.

That day, I didn’t just watch. I sat down. He handed me a dull knife and a small leather sheet. “Try,” he said, smiling. It took me 20 minutes to ruin a dragon tail. But I didn’t care. We laughed. His apprentice adjusted my grip. That moment stayed with me longer than any museum did. This is the kind of experience China world heritage sites now quietly offer—if you know where to look.

You can find these workshops in Xi’an’s Muslim Quarter or near Gao’s Grand Courtyard, with entry and session fees around 50–80 RMB. Many guides on Ctrip list them as “intangible cultural experience” tours. Hotels like Eastern House Boutique Hotel welcome foreigners, and staff will gladly book slots or call the artists directly. Language isn’t a wall here—your hands do the talking.

Take a Garden Class in Suzhou, Learn the Philosophy of Stones

Suzhou’s classical gardens aren’t random. Every stone, pond, or zigzag bridge has purpose. But what if you could learn the rules—and then break them a little? That’s what I did at Master of the Nets Garden, where a soft-spoken volunteer invited me to join a local gardening group. We weren’t planting anything. We were learning to position stones—like writing poetry with rocks.

They explained: a good rock must be “leaky, thin, wrinkled, and transparent.” It should feel like a mountain, even if it’s palm-sized. I spent 90 minutes arranging rocks beside a tiny fake stream while a retired teacher named Mr. Lu circled around, correcting angles gently. “It’s not how it looks,” he told me. “It’s how it feels.” Few China world heritage sites let you bend down and build a piece of the place.

Most major gardens now host these mini-sessions, especially in the off-season. Entry costs 30–90 RMB, and garden staff often speak basic English. The Suzhou Museum, designed by I.M. Pei, sometimes offers bilingual tours and “design your own rock garden” classes. Hotels like Pan Pacific Suzhou are used to foreign guests and often include cultural bookings in their packages. I never imagined learning landscape philosophy from gravel. But here I am, still thinking about it.

Hike the Great Wall at Jinshanling and Camp Under the Stars

Sure, you’ve seen a hundred Great Wall photos. But here’s one you haven’t: stars overhead, crickets chirping, your sleeping bag unrolled next to a broken tower, and silence so wide you forget your own name. That was my night on the Jinshanling section, where ruggedness beats beauty and tourists are rare after sunset.

This part of the Wall is less restored, more real. The stones shift underfoot. The watchtowers crumble a bit. But that’s the appeal. Hiking here takes about 2–3 hours, depending on pace, and you can join a guided overnight tour (around 600–900 RMB) that sets up tents, dinner, and breakfast. One couple I met brought their daughter—it was her first time seeing the Milky Way. She just whispered, “Is that… real?” I almost cried.

Among all China world heritage sites, the Wall may be the most photographed—but hiking it, sweating on it, sleeping beside it? That hits different. From Beijing, take a bus to Gubeikou or arrange private transport via your hotel (most can help). The Great Wall Fresh Farmstay and Xiaolumian Inn both accept foreigners and offer local food after the trek. There’s no gift shop up there—just wind, sky, and time.

- shadow play

- Great Wall

Which Sites Deserve More Than a Day Trip?

Pingyao: China’s Financial Capital That Time Froze

Some towns pretend to be old. Pingyao just stayed that way. This ancient walled city in Shanxi province was once the financial heart of imperial China, home to the country’s first draft bank. Today? It’s still got that 19th-century energy, but slower, dustier, and somehow sweeter.

You walk along the city wall—yes, you can still walk the whole thing—and peer down at narrow lanes lined with red lanterns and quiet courtyards. I stayed at Yide Guesthouse, a former merchant’s home turned inn. The staff welcomed me in English, handed me jasmine tea, and pointed out their ancestral altar in the back. That night, I wandered into a shadow puppet show in a tiny theatre. No ticket. Just a stool and applause.

Pingyao is among those China world heritage sites where it’s best to stay at least two nights. Trains from Beijing or Xi’an take 3–4 hours, tickets from 150–200 RMB. Entry to the ancient city is 125 RMB, covering multiple sites. Most guesthouses accept foreign travelers, and many display a blue 外宾接待标志 ("Foreigner welcome" sticker). One tip? Go in early fall. The sky turns copper and the lanterns burn brighter.

Fujian Tulou: Living in a Fortress of Clay and Family

If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to live in a doughnut-shaped castle, welcome to the world of Fujian tulou. These massive earthen buildings, once home to Hakka clans, are like rural spaceships grounded in misty hills. One building can house 300 people. It’s loud, layered, and smells like smoke and rice.

The best part? You can actually stay in one. I booked a night in Tianluokeng Tulou Cluster, where my host, Auntie Lin, showed me how to wrap taro leaves and boil peanuts in clay pots. Kids played badminton in the round courtyard. Chickens wandered past my suitcase. It wasn’t quiet—but it felt like home. And unlike many China world heritage sites, this one hasn’t been turned into a showcase. People still live, eat, and argue here.

To get there, fly into Xiamen, then take a 3-hour bus or private transfer. Expect to pay around 60–100 RMB for entry, and 200–400 RMB for a night’s stay, including meals. Some tulou inns have English signs, but communication leans on smiles and translation apps. Honestly, if you want an unplugged, full-body memory? One night inside the tulou is worth more than any five-star hotel.

West Lake, Hangzhou: Not Just Scenic, But Poetic

Sure, you’ve seen lakes before. But have you seen one that writes poems at you? That’s West Lake in Hangzhou—a body of water so famous it’s inspired emperors, monks, and Starbucks baristas who sketch it on cups. Walking its causeways at dawn, with mist on the water and pagodas glowing faintly in the distance, felt like being inside an ink painting.

Unlike some China world heritage sites, West Lake is woven into the modern city. Locals jog beside ancient bridges. Students recite Tang poetry on rented paddle boats. You don’t need a tour guide here. Just follow the willow trees. Key spots like Broken Bridge, Leifeng Pagoda, and Three Pools Mirroring the Moon are easy to find. The best way? Rent a bike, loop the lake, stop when you feel something shift.

Hangzhou is well connected—high-speed trains from Shanghai take under 1 hour and cost 50–80 RMB. The lake is public, but entry to museums and pagodas ranges from 30–60 RMB. Hotels like Midtown Shangri-La Hangzhou are foreign-guest approved and offer lake-view rooms. I stayed for two nights and left with 50 photos and a half-written haiku.

- Pingyao Ancient Town

- Hangzhou West Lake

How Do China’s Heritage Sites Reflect Its People?

The Panda Sanctuaries Aren’t Just Cute

The first time someone hears “China world heritage sites,” they probably picture temples or palaces. But what if I told you that one of the most emotionally powerful is a forest full of bamboo and bears? The Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries are more than just a haven for panda lovers—they’re a mirror of how China sees nature and itself. You don’t just stare at sleepy black-and-white creatures. You start to see how conservation, identity, and even diplomacy all wrap into this surprisingly soft symbol.

Unlike your usual zoo visit, the moment you walk into Wolong or Bifengxia, it feels… quieter. Deeper. It’s not just the pandas; it’s the monks nearby who light incense every morning. The way the caretakers explain panda behavior feels spiritual, not rehearsed. There’s something oddly grounding about it all—especially when you hear that this sanctuary houses more than 30% of the world’s wild pandas. That’s no small number. That’s national responsibility.

Foreign visitors often say they go expecting a cute photo and leave with a quiet kind of awe. These China world heritage sites offer that unexpected layer—they aren’t about monuments, but values. I don’t know, there’s something about the way a nation protects its animals that tells you how it treats its soul.

Leshan Giant Buddha and the Mountain Monks

You’ve probably seen the photo: a colossal Buddha carved into a red cliff, toes bigger than most people. That’s Leshan. But what Instagram doesn’t show you is the journey it takes to understand it. This isn’t just about size—it’s about silence. The silence monks have kept alive for over 1,300 years since this Buddha began watching over the river.

The minute you arrive, it’s not the statue that hits you—it’s the slope. The narrow staircase, the moss-covered railings, the sudden quiet even among tourists. You pass small shrines on the way down, often unnoticed. Some monks still live in the adjacent Lingyun Temple, which you can visit. And if you're lucky, you might even hear their low chants drifting over the river fog. It’s eerie in the best way.

China world heritage sites like this show how deeply belief still shapes landscapes. They’re not static “places to visit.” They’re active, pulsing expressions of identity. People still light candles here for luck. Still whisper names of loved ones. Still believe in something larger than themselves. That’s not history—it’s presence.

The Tea Horse Road Isn’t Lost—It’s Alive in Lijiang and Beyond

So here’s a fun contradiction: one of the most “ancient” trade routes in China is also one of the most alive. The Tea Horse Road—an old trail that once traded Tibetan horses for Chinese tea—still winds through cobbled streets and mountain passes in Yunnan and Sichuan. Some of it is gone. But much is still walked today, especially in towns like Lijiang or Shaxi. And walking it? That feels like flipping pages of a novel with your feet.

In Lijiang’s old town, you see traces of the road not in signs, but in stories. Elder Naxi women weaving on porches. Shops selling bricks of pu’erh tea aged longer than your last three relationships. Horses carrying tourists now, yes—but the trail under their hooves hasn’t changed. You can even hike sections of it, like from Lijiang to Baisha, passing villages untouched by modern highways.

I think that’s the core of china world heritage sites: they let you live side-by-side with the past without sealing it in glass. You’re not a spectator. You walk, smell, and maybe—if you’re lucky—share a bowl of butter tea with a stranger. And you remember it because it’s messy, human, and completely unfiltered.

- Giant Panda Base

- Leshan Giant Buddha

Is Heritage Tourism Changing in China?

Heritage tourism in China used to feel like ticking boxes—Great Wall? Check. Forbidden City? Check. But lately, things are shifting. Travelers are slowing down. Locals are pushing back. Technology’s stepping in. Even UNESCO sites are being reimagined. If you’re wondering what this means for future visitors, or how it changes your trip, here’s what’s happening beneath the surface of those ancient stones.

From Checklists to Slow Immersion

Remember the guidebook-style itinerary: six spots in one day, 300 photos, zero memories? That’s fading. Both Chinese and foreign visitors are ditching checklist tourism for what locals now call “深度游” (deep travel). Instead of rushing through the Terracotta Warriors, they take a few hours to try pottery in a Xi’an courtyard. Or they visit Chengdu’s Wuhou Shrine, then grab tea with retirees in a nearby alley.

Part of this is generational. Young Chinese travelers care less about “proof” on social media and more about moments that feel genuine. Foreign travelers, too, are realizing that China world heritage sites aren’t just “ancient buildings”—they’re living spaces. You now see people spending a whole day just walking around Pingyao or sketching by West Lake.

Tour operators are catching up. New platforms like Qyer and Ctrip’s “local life” section now offer multi-day “heritage living” experiences. Prices vary—from 400 RMB for a guided walk to 1500+ RMB for immersive two-day stays with locals. The shift feels slow, but also solid. It’s not a trend. It’s a change of pace that might just stay.

The Rise of Digital Heritage and Virtual Reconstruction

Can’t make it to a remote Buddhist cave? No problem—China’s digitizing its treasures. With support from UNESCO and institutes like Dunhuang Academy, you can now explore Mogao Grottoes online, right down to the last painted eyebrow on a Tang Dynasty mural. It’s wild.

In fact, digital tools are now part of the China world heritage sites experience itself. At the Forbidden City, you can scan a QR code and see 3D models of how emperors lived. At Suzhou Gardens, AR headsets show how the same corner looked in the Qing Dynasty. Even local museums have started offering WeChat mini-programs with multilingual guides, real-time maps, and story-based narration.

It’s not replacing the real thing—but it makes the visit more layered. For travelers who don’t speak Chinese or can't handle complex site layouts, this stuff is a game-changer. And it helps protect fragile sites too. Instead of cramming 10,000 people into one cave, many now explore digitally, which eases tourism pressure and preserves what matters most.

Still, some purists say this removes the “magic” of being there. But maybe, just maybe, digital heritage helps more people fall in love before they even arrive.

Challenges: Tourism Pressure and the Risk of Over-Commercialization

Let’s be honest—some China world heritage sites are buckling under the weight of their own popularity. You see it in Lijiang’s crowded old town, where every shop sells the same scarf. Or in Fenghuang, where folk songs have been turned into stage shows for ticket sales.

Tourism brings money, yes. But it also risks flattening culture into a product. Locals complain about rising rents, noise, and being reduced to “props” in photo ops. In Suzhou, real artisans are being replaced by souvenir factories. And some tulou villages now have more selfie sticks than locals.

China’s response? Mixed. Some sites have limited daily entries—like Jiuzhaigou (now capped at 41,000 people/day, according to the official tourism bureau link). Others like Pingyao are investing in community-based tourism, where locals host tours and keep profits.

The real risk is loss of authenticity. When a tea ceremony becomes a scripted show, something’s lost. But with rising awareness and traveler pushback, there’s hope. As long as we keep asking the right questions—what’s real, who benefits, and why it matters—we might just get it right.

- Scan the QR code to view the “live” cultural relics

- Museum AR smart tour guide service

What’s My Favorite China World Heritage Memory?

It wasn’t on any itinerary. No sign pointed me there. I was just walking through Pingyao at night, past lantern-lit alleyways and closed shopfronts, when I heard it—a soft pluck of strings, then a voice. I turned and saw a woman, maybe in her sixties, sitting in the shadow of a temple, playing a two-string erhu. No crowd. No show. Just her and the stone around her.

That’s the thing about China world heritage sites—sometimes the most powerful moments aren’t the ones in the brochures. I’d seen the ancient city walls. I’d taken the photos. But that sound, echoing off Ming Dynasty bricks under flickering red light, hit different. It made the place feel less like a museum and more like a memory you didn’t know you had.

Later, I learned that she wasn’t a performer. Just someone who lived nearby. Her father had played erhu in the 1940s. She said she came out when the streets were quiet, when the air felt “like old times.” It wasn’t for tips. She didn’t even want an audience. “The stones still remember,” she said, smiling. “You just have to wait for them to speak.”

Would you call that a highlight? I don’t know. But for me, it was the clearest reminder that China’s heritage isn’t just ancient—it’s alive. And sometimes, it plays music at midnight, when no one’s looking.

Pingyao Ancient Town at night

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How many World Heritage Sites are there in China?

As of 2025, China has 57 UNESCO World Heritage Sites—including 39 cultural, 14 natural, and 4 mixed properties. That puts China just behind Italy in total numbers, but far ahead in terms of cultural diversity and continuity. New entries like the Ancient Tea Plantations of Jingmai Mountain show how China blends natural landscapes with millennia-old practices. What stands out isn’t just preservation—it’s how daily life still happens within these heritage zones. In places like Lijiang or Pingyao, people live, trade, and celebrate festivals just like their ancestors did—only now with Wi-Fi and tourists watching quietly from the sidelines.

Q: What country has the most world heritage sites?

As of 2025, Italy leads with 59 World Heritage Sites, followed closely by China with 57, and Germany with 52. But numbers only tell half the story. If you're interested in living heritage—places where people still practice ancestral customs, speak regional dialects, or grow ancient crops—China’s world heritage sites might give you a deeper, more layered travel experience. Think of tea-picking in Yunnan, calligraphy classes in Beijing's hutongs, or even dragon dances during Lantern Festival in historical city cores.

Q: Why is the Great Wall of China considered a World Heritage Site?

The Great Wall was designated by UNESCO in 1987, not just because of its length (over 21,000 km!) or age (some parts date back to the 7th century BC), but because it symbolizes dynastic ambition, military innovation, and cultural unity. It’s not one continuous wall either—there are many sections built over different dynasties. Sites like Badaling and Jinshanling are still popular today for their scenic hikes and preserved Ming-era architecture. Entrance fees range from 40–65 RMB, and yes—English signs and guides are widely available.

Q: What is the Tusi Site and why is it important?

Most travelers haven’t heard of the Tusi Sites, and that’s part of the charm. These are former centers of rule under hereditary tribal chieftains in southwest China—recognized by UNESCO in 2015 for showcasing China’s multi-ethnic governance model. They’re located across Hunan, Guizhou, and Yunnan, and include stone fortresses, ancestral temples, and ceremonial platforms. You might catch a local ritual or see carved histories in Dongba script. These aren’t just ruins—they’re entry points into China’s minority stories, often overlooked in mainstream history books.

Q: Which World Heritage Sites in China are best for hands-on cultural experiences?

If you want to do more than just look—Suzhou, Lijiang, and Fujian’s Tulou are ideal. In Suzhou, you can join embroidery workshops or learn the art of bonsai pruning inside classical gardens. In Lijiang, local Naxi families open their homes for tea ceremonies and music performances. And the tulou? You don’t just visit them—you sleep in them. These mud-brick clan houses still host multi-generational families, and some rooms are now cozy guesthouses welcoming foreign travelers. It’s one thing to read about heritage—it’s another to fall asleep to the sound of wooden shutters closing in a UNESCO-listed building.

🛏️ Note: Tulou stays are often around 150–300 RMB per night, and most now accept foreign passport holders.

Q: How can I explore lesser-known China World Heritage Sites?

The big names like the Forbidden City are stunning, but if you’ve got more time—or just less love for crowds—head toward China’s quieter side. Pingyao, for example, feels like walking inside a scroll painting, especially during lantern season. Mount Wudang offers Taoist temples and martial arts schools, while the Chengjiang Fossil Site in Yunnan has remains dating back 520 million years. These places may not trend on Instagram, but they’re the ones that stick in memory. Buses or fast trains can get you there, and in many cases, entry is under 100 RMB.

🚄 Travel tip: Chengjiang is accessible by bus from Kunming East Station, about 2 hours one way.

Q: How can I plan a trip to China’s living heritage sites?

Planning a heritage-focused trip isn’t just about ticking off famous names—it’s about choosing places where you can engage, not just observe. Start with a shortlist: maybe Xi’an for shadow puppets, Suzhou for garden classes, or Yunnan for tea and Naxi rituals. Book accommodations that allow foreign guests (most do now, but always check), and see if there are local tours that skip big buses. Want a tip? Time your visit around traditional festivals—Qingming in Hangzhou or Mid-Autumn in Pingyao will show you a side of China that rarely makes it into guidebooks. Most importantly, leave space in your itinerary to get lost a little—it’s often where the best stories start.